Endodontic Microsurgery: The Significance of Soft Tissue Management in Overall Success

By Mike Sabeti, D.D.S.

By Mike Sabeti, D.D.S.

Reported tooth survival after root canal treatment ranges between 86% and 93%1. Even with such high success rates, there is a possibility of failure. When primary root canal therapy is not successful, the persistent infection can be treated with one of three treatment options: nonsurgical retreatment, surgical endodontics, and extraction followed by placement of an implant or a bridge. With the emergence of modern approach techniques, magnification aids, and biocompatible materials, Periapical Surgery Treatment (PAST) has been favored as a treatment of choice for treating periapical lesions and saving natural dentition. When PAST is compared to other treatment options, a full understanding of the treatment outcome and prognosis of the procedure is crucial to provide the best treatment plan and clinical patient care with high evidence2 This paper outlines the importance of surgical factors on long-term prognosis and patient satisfaction focusing on the importance of soft tissue management during the procedure.

At its core, periapical surgery treatment is the removal of a periapical lesion by resecting the apical portion of the root followed by disinfection and sealing of the apical portion of the remaining root canal3. Yet, before any of this can be done, access to the apex must be made through creation of a well-designed gingival flap. Soft tissue outcome is greatly influenced by various factors which are an appropriate flap design, flap elevation, flap advancement, wound closure, stability of the wound, and post-operative care.

A successful and sound flap design require taking a big picture view of healing, Just as a neuro or cardiac surgeon plans their approach before making their first cut, successful endodontic surgical technique depends on an appropriate flap design prior to placement of any incision. An appropriate flap design should provide good surgical access and visibility. Morphological characteristics of the periodontium, tooth morphology, interdental papilla, smile line, osseous architecture, blood supply, type of restoration and anatomical structure will dictate the boundary of incision and guide the shape of the flap.

A surgeon should anticipate potential failure prior to the surgery and not ignore the potential for failure or a problematic outcome. Shallow vestibules, muscle attachment and frenum pull may alter the plan for type of the flap design. Any dehiscence or fenestration or amount of bone loss covering the area must be identified to elevate esthetic area concerns from healing. This should also be identified for any existing pontics and crown margins to avoid compromising the healing of soft tissue. Finally, identifying the biotype and bioforms of tissue will help the planned flap and further improve outcomes.

After meticulous planning, the use or proper technique when finally raising the flap comes down to execution of all the considerations listed prior. Unlike periodontal surgery, in endodontic microsurgery the tissue being operated on is healthy and its healing can be enhanced by maintaining the layer of vital tissues, epithelium and connective tissue. Healing can be further optimized by retaining cortical periosteal tissue, avoiding curettage of remained vital tissue, evading damage and dehydration of mucoperiosteal flap.

Prior to any incision, a surgeon should decide the length and location of the incision. Multiple attempts to reach the desired depth and length will create jagged edges. By knowing the number of teeth included, length of the roots, the extent of the periapical lesion and location of any vital structures during planning, the surgeon will prevent any jagged edges from compromising the healing of a mucoperiosteal flap.

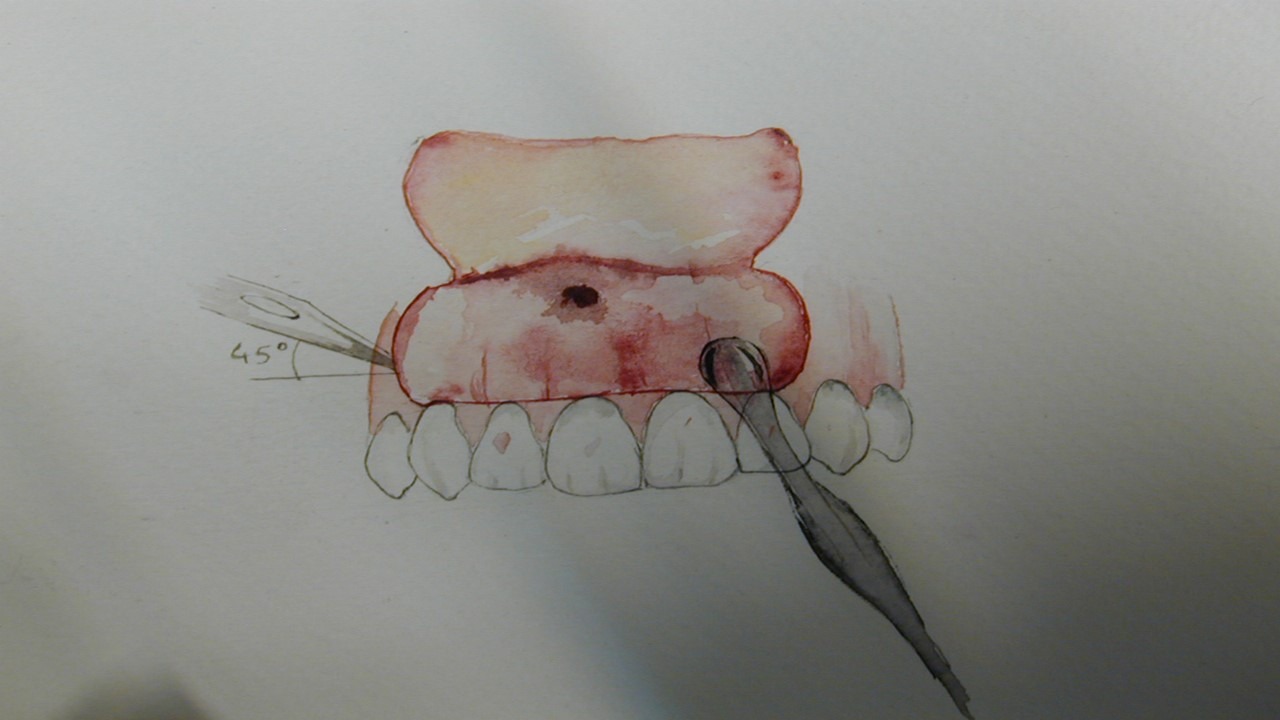

Flaps should be reflected with minimal trauma to minimize any compromise to the blood supply. Designing a sound surgical techniques and achieving a successful outcome from the flap preparation requires knowledge of anatomical structure such as depth of the vestibule, thickness of the cortical plate, mental foramen, alveolar recess, maalar (zygomatic) process, exostoses, alveolar recess, muscle attachments, the maxillary antrum and major arteries. The critical flap ratio of width to length that width should be approximately twice as length4. Reflection and suturing of the flap should be achieved passively. To begin, a short incision makes retraction difficult, and result in trauma with possible tearing of the flap. A larger flap prevents tear and trauma, provides more access and visibility of the surgical site. While staying within the anatomical boundaries, a larger flap will aid in the procedure and outcome. When closing the tissue, adequate movement without any tension, stretch or force and remaining of a flap in its position after suturing even when lips and tongue move are essential in a primary intention healing of a mucoperiosteal flap (Figure 1).

Figure 1

A sound surgical flap technique dictate the reapproximation and primary closure of mucoperiosteal flap. A vertical incision will be made in the form of a c-shape and will extend at least 4mm apical to the margin of the bony defect. Vertical incisions should be placed at the most distal (most distant proximal) line angle of the tooth in order to use the adjacent unincised papilla for suturing (Figure 2). The incision usually extends two teeth beyond the target tooth mesial and distal. The C-shape vertical incisions are composed of a horizontal component at the coronal part (Figure 2), an internally curved component at the mid-part within the mucosa (Figure 3). The advantage of the c shape incision is that it gives more access and better flexibility for repositioning the flap than straight vertical incisions. The horizontal component improves tissue adaptation at closure. The internally curved and cut back components provide flap flexibility and reduce the tension by increasing the length of the incision. Using blunt dissection, a mucoperiosteal flap is carefully reflected away to expose the bony margin of the defect.

Figure 2

Figure 3

In conclusion, endodontic surgery requires anticipation of potential failure prior to treatment to properly access each anatomical veriation and ensure the best surgical result for periodontal healing and future restorative considerations.

References:

- Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K (2010) Tooth survival following non-surgical root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. International endodontic journal 43(3), 171-189.

- Gutmann JL, Harrison JW. Surgical Endodontics. Boston, MA, USA: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1991.

- Richards D, Clarkson J, Matthews D, Niederman R. Evidence-based dentistry: managing information for better practice. London, Chicago: Quintessence Pub; 2008.

- Mörmann W, Ciancio SG. Blood supply of human gingiva following periodontal surgery. A fluorescein angiographic study. J Periodontol 1977; 48:681-692.

Dr. Mike Sabeti currently serves as Director of post graduate endodontics at University of California at San Francisco. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics. He has made many invited presentations and published along with several textbook chapters and textbooks. In addition, he has received a Certificate in Recognition of Outstanding Services as a Faculty Member to the enhancement of education and clinical excellence, presented by the Advance Endodontics Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of University of Southern California, and Certificate of Appreciation for the Service and Significant Contribution to Periodontal Division, University of Texas. Dental Branch. He was honored by Haile T. Debas Academy of Medical Educators at University of California San Francisco with an Excellence in teaching awards.