Associate Corner: Respecting Patient and Doctor Autonomy

By Dr. Helen Yang Meyer

By Dr. Helen Yang Meyer

Each of us young endodontists will need to decide our own line between appropriate treatment with a questionable prognosis (given informed consent) and inappropriate treatment. Don’t let a patient (or anyone else) pressure you into doing treatment you believe is wrong. To that end, I’d like to share a recent patient encounter that taxed my ability to stand my ground in different ways.

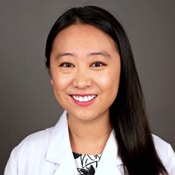

A female patient with unremarkable medical history first presented for evaluation three months ago for tooth #30. The bitewing radiograph (Image 1) showed distal caries extending nearly to the pulp, and clinically there was a cavitated, carious lesion. At the time, the patient was asymptomatic, and the tooth tested normal to all pulp tests. The diagnosis was asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis/ normal apical tissues.

Image 1: Bitewing radiograph taken January 2021 on initial presentation showing #30 with deep distal caries

I explained it likely needs endodontic treatment in the foreseeable future and reviewed the rationale for recommending RCT. However, she had read about vital pulp therapy on her own and came armed with fairly smart questions. She was reluctant “to kill a perfectly good nerve and blood supply” and “weaken the tooth unnecessarily,” as she put it. I mentioned the alternative of first attempting a direct restoration, possibly a pulp cap or pulpotomy, as well as symptoms of pulpitis to monitor. We spent 30 minutes chatting and drawing diagrams over her x-rays.

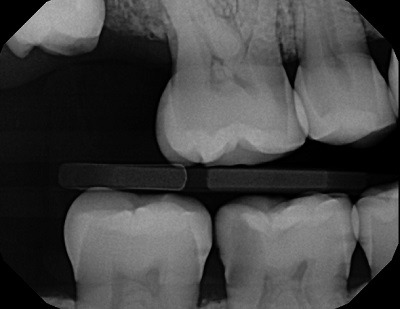

Last week, she finally saw her general dentist to restore the tooth, after experiencing tooth throbbing for a few days. The dentist unsurprisingly encountered a pulp exposure, placed a cotton pellet and glass ionomer, and referred the patient back to me (see image 2).

Image 2: Periapical image taken April 2021 following caries excavation, pulp exposure, and temporary filling placement

That afternoon, she insisted on only treating the distal root and leaving the mesial root untreated. She was adamant that the nerve was still alive because the tooth was still cold sensitive, that there was value to leaving the mesial nerve alone, and that accessing the mesial root would greatly weaken the tooth. She claimed I told her a partial root canal was possible.

I was firm that I would not treat only half the tooth because 1) incomplete treatment would not resolve her symptoms, 2) the treatment would eventually fail and the tooth would likely acquire an avoidable infection, 3) it’s below the standard of care and other dentists would be rightly critical. A fourth reason I didn’t mention was that insurance was unlikely to pay for half a root canal.

Cue another extensive back and forth exchange during which she crossed her arms and tried a variety of approaches: “I might as well get the tooth pulled since there won’t be any tooth left after you drill on it too,” “Explain again how this [mesial] root is bad,” “Don’t I have the right to choose how far you drill?” “I guess I’ve got no choice of how the root canal will be done,” and eventually “I don’t want to do this, but go ahead.”

In these cases where patients don’t want to take ownership of their decisions, I find it helpful to emphasize patient autonomy. I explained that she HAS valid options to choose between: Endodontic treatment (in the manner I proposed), extraction, or holding off treatment. As we had not yet started treatment, she had every right to change her mind.

I reassured her she shouldn’t feel badly for asking smart questions and that I was glad we were taking the time to get on the same page. I said she would not be charged today if she decided against treatment. Bottom line was I needed her to be fully onboard and want the RCT herself before moving forward with treatment.

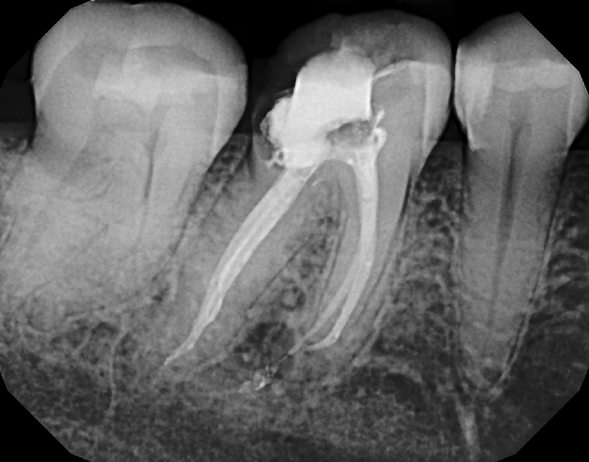

The patient ultimately decided to proceed with the RCT. I asked her to doubly confirm that this was indeed what she wanted to do, obtained verbal and written consent, and proceeded with treating what ended up being a very challenging four canaled molar and ending the day 45 minutes late (image 3).

Image 3: Post-treatment radiograph

The ADA principle of patient autonomy states that doctors have “a duty to treat the patient according to the patient’s desires, within the bounds of accepted treatment, and to protect the patient’s confidentiality.” I tried my best to steer her towards one of the options I believe was appropriate, while respecting her thinking and autonomy. Perhaps we could have arrived at an endpoint more efficiently, with less back and forth. I welcome suggestions from readers and more experienced endodontists on your go-to phrases to move the conversation along in the best interests of the patient.