Considerations for Pain Management in Pediatric Patients

By Gabriella Blazquez. Introduction by Dr. Moein Sadrkhani.

In most residencies, we provide root canal treatments for our pediatric patients, which sometimes can be challenging.

This is a great piece by our student contributor Gabriella Blazquez (UConn School of Dental Medicine 2022), which hopefully will help everyone provide better treatments to our crumb-cruncher patients.

I know we have few residents who have finished their pediatric residencies and currently are endodontics residents — I am very eager to hear your take on these considerations:

There are many reasons a child may present to an endodontist for treatment. Inflammation and infection resulting from deep decay or dental trauma are among the most common reasons. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 13% of adolescents (ages 12 to 19) and 20% of children (ages 5 to 11) have at least one untreated decayed tooth. Additionally, about one in five children and adolescents in the Americas experiences some form of dental trauma. Due to the high prevalence of decay and dental injury in young people, it is critical for endodontists to be comfortable treating children and adolescents.

There are many reasons a child may present to an endodontist for treatment. Inflammation and infection resulting from deep decay or dental trauma are among the most common reasons. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 13% of adolescents (ages 12 to 19) and 20% of children (ages 5 to 11) have at least one untreated decayed tooth. Additionally, about one in five children and adolescents in the Americas experiences some form of dental trauma. Due to the high prevalence of decay and dental injury in young people, it is critical for endodontists to be comfortable treating children and adolescents.

The field of pain management and behavior modification in children is a broad one. My goal in this article is to summarize a few concepts I have found helpful when seeing pediatric patients. I believe that these simple tips can be useful adjuncts to an endodontist’s usual repertoire when seeing young patients.

Fostering a Comfortable Environment

When treating children, the focus should be on supporting the child and fostering an environment centered on learning which minimizes anxiety. Creating such an environment in endodontics must include achieving profound anesthesia prior to initiating treatment. Injections are often cited as the most feared aspect of dental treatment. However, delivery of anesthetic can be made less painful via distraction (jiggling the patient’s cheek), buffering the local anesthetic, and decreasing the rate at which anesthetic is delivered.

Additionally, anxiety can be reduced by using the Tell-Show-Do (TSD) graded exposure technique, which introduces patients to instruments and sensations in a systematic manner. Explaining and then demonstrating a part of the treatment before proceeding allows the child to understand and prepare for what will be happening. For example, before giving an injection of local anesthesia, you can tell the child what materials and motions will occur. Use developmentally appropriate language to explain the importance of numbing the area and tell them how it will feel (e.g. heavy, tingly). Afterwards, you can show the child relevant instruments such as: the topical gel, the carpule of anesthetic, and the suction. You can also show them the motion by having them relax, open wide, and lightly pressing where the anesthesia will be applied with a cotton swab. Then, when they feel that they understand what will be happening and why, you can move forward with the procedure.

Also, structuring time can be helpful in giving the child a roadmap of what the visit will entail. For example, “First, I will explain the treatment; you’ll then have time to ask any questions you might have. After that, your mom will hold your hand and we’ll get started when you feel ready. When we’re done cleaning your tooth and placing the medicine, you’ll be free to enjoy the rest of the day.”

Depending on the child’s personality and individual needs, you may be able to give them choices which can enhance their sense of control and decrease feelings of vulnerability. For example, you may let the child choose the color of the rubber dam, the flavor of topical anesthetic, or what will be playing on the television. Distraction, usually with music or imagery, is another tool which can be useful in children. However, it should be avoided in those who are particularly anxious or hypervigilant. When employing Tell-Show-Do, using structuring, providing choices or distractions remember to use developmentally appropriate language.

Assessing Pain in Children:

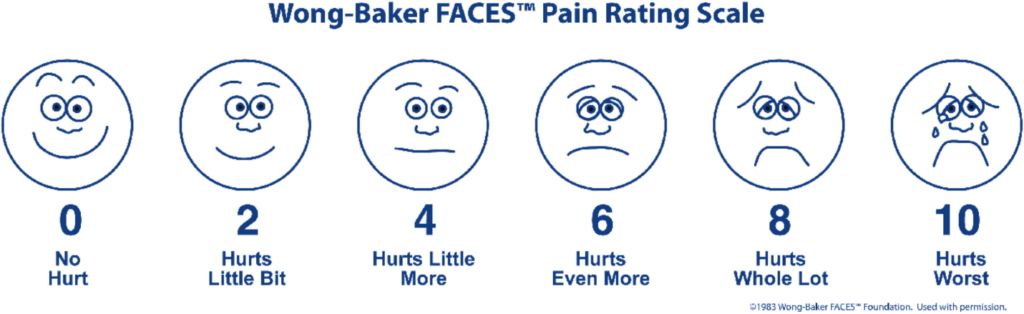

Pain assessment allows the provider to identify and evaluate pain during treatment. Age-appropriate scales should be used whenever possible. For example, in children between 4 and 6 years old, the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBS) in combination with some form of behavioral rating is the most common form of assessment. The WBS is used in children to rate pain severity using a visual analog scale of facial expressions which range from comfortable to extremely distressed. Based on the faces and written descriptions shown below, the patient can point to the image which best matches how they are feeling. In addition to having the patient describe their pain level, it can often be helpful for the provider to recognize behavioral changes as signs of discomfort, especially in pediatric patients. Different forms of behavioral rating exist including the Frankl and Venham rating scales. One of the most widely used behavior evaluation scales is Frankl’s rating scale, which rates a child’s behavior on a scale of 1 to 4.

Figure 1. Example of the visual analog scale (VAS) used in the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBS).

Figure 2. Frankl’s behavior rating scale.

| 1. | Definitely negative refusal of treatment, crying forcefully, fearful, or any other overt evidence of extreme negativism |

| 2. | Negative reluctant to accept treatment, uncooperative, some evidence of negative attitude but not pronounced, i.e., sullen, withdrawn |

| 3. | Positive acceptance of treatment; at times curious, willingness to comply with the dentist, at times with reservation but patient follows the dentist’s directions cooperatively |

| 4. | Definitely positive good rapport with the dentist, interested in the dental procedures, and laughing and enjoying the situation |

For children with limited communication skills, behavior rating scales and physiologic reactions (ex. heart rate, perspiration) can often be employed together. Observing a child’s facial expressions, behavior, and physiologic reactions can be useful in identifying discomfort and accessing the efficacy of subsequent interventions.

Addressing Discomfort

Children often lack the emotional maturity and communication skills to appropriately verbalize discomfort. Therefore, we should be hyper-vigilant for nonverbal signs of pain, including changes in facial expressions, behavior, and physiological markers. Responding immediately to these signals can give a child a better sense of safety and control.

Appropriate ways to address discomfort include pausing the procedure, when it is safe to do so, sitting the child up, and asking them to explain how they are feeling. Every effort should be made, at this point, to identify and address the source of pain or anxiety. This can be done using both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic techniques intra-operatively.

Acetaminophen and NSAIDs should be considered the first line therapy for post-operative management of pain following endodontic treatment in pediatric patients. Providers should note the potential risks and of NSAIDs, for example their ability to induce asthma/bronchoconstriction in susceptible patients. The use of opioids should be rare and only prescribed to young patients after thorough screening of both the patient and parents concerning history of opioid use. Providers should note that opioids should not be used in patients also taking benzodiazepines.

Conclusions

When treating pediatric patients in an endodontic setting, the provider should strive to foster a comfortable environment by pursuing patient understanding and acceptance, assessing pain status, and addressing any discomfort, which may arise. Helpful modalities, which may help achieve these goals, include achieving profound anesthesia preemptively, Tell-Show-Do (TSD), time structuring, distraction, continuous pain assessment, and the use of non-pharmacological and pharmacological pain management.

References:

- Dye BA, Xianfen L, Beltrán-Aguilar ED. Selected Oral Health Indicators in the United States 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief, no. 96. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012.

- Azami-Aghdash S, Ebadifard Azar F, Pournaghi Azar F, et al. Prevalence, etiology, and types of dental trauma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29(4):234. Published 2015 Jul 10.

- Dowd F. Mosby’s Review for the NBDE Part II.St. Louis, Mo, USA: Mosby; 2007

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pain management in infants, children, adolescents, and individuals with special health care Needs. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2020:362-70.

- Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale–Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain2001;93:173–83.

- Young KD. Pediatric procedural pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Feb;45(2):160-71. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.019. PMID: 15671974.

- FranklSN, ShiereFR, Fogels HR. Should the parent remain with the child in the dental operatory? J Dent Child. 1962;29:150-63.

- Garra G, Singer AJ, Taira BR, Chohan J, Cardoz H, Chisena E, Thode HC Jr. Validation of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale in pediatric emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Jan;17(1):50-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00620.x. Epub 2009 Dec 9. PMID: 20003121.

- Savino F, Vagliano L, Ceratto S, Viviani F, Miniero R, Ricceri F. Pain assessment in children undergoing venipuncture: the Wong-Baker faces scale versus skin conductance fluctuations. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 12;1:e37. doi: 10.7717/peerj.37. PMID: 23638373; PMCID: PMC3628989.

- McGrath PJ, Unruh AM. Measurement and assessment of pediatric pain. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, Tracey I, Turk DC, eds. Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Saunders; 2013: 320-7.

- Levy S, Volans G. The use of analgesics in patients with asthma. Drug Saf. 2001;24(11):829-41. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124110-00004. PMID: 11665870.

- Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, Comer SD. Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med. 2013 Jul;125(4):115-30. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2684. PMID: 23933900; PMCID: PMC4057040.

- Oosterink FM, de Jongh A, Hoogstraten J, Aartman IH. The Level of Exposure-Dental Experiences Questionnaire (LOE-DEQ): a measure of severity of exposure to distressing dental events. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008 Aug;116(4):353-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00542.x. PMID: 18705803.

Gabriella Blazquez is a student from UConn School of Dental Medicine (2022). She is interested in endodontics and delightfully enjoys reading and contributing to our newsletter.