Endodontic Surgery: A Historical Perspective, Part 2

Presidential History

Recently, when attending a committee meeting at our AAE headquarters, I had the privilege of touring the new office. I was impressed with the way in which the office was decorated – specifically, the multiple tributes to AAE pioneers whose dedication and innovation helped create the incredible association that AAE is today. One of these pioneers was the association’s first president, Dr. W. Clyde Davis (1943-1944), whose photograph is framed in the office. Since our current president, Dr. Stefan Zweig, was also in attendance at this meeting, I asked if I could take a picture of him in front of Dr. Davis’ photo. We thought it would be fitting to include this picture here, as a testament to AAE’s presidential history before we begin our discussion of the history of endodontic surgery. -Bradley H. Gettleman, D.D.S., M.S

Endodontic Surgery: A Historical Perspective, Part 2

By Bradley H. Gettleman, D.D.S., M.S.; Moein Sadrkhani, D.D.S., M.S.; and Jessica N. Gettleman, M.S.

By definition, most endodontic treatment would fall into the category of surgery, otherwise known as the branch of medicine that employs operations in the treatment of disease or injury. Surgery can involve cutting, abrading, suturing, or otherwise physically changing body tissues or organs. However, for the purpose of this paper, we will limit our definitions to nonsurgical and surgical endodontic therapy. While nonsurgical treatment refers to procedures performed through a coronal access cavity preparation, “endodontic surgery” is defined as endodontic treatment via direct access to the apex and periradicular area of the tooth.

Periradicular surgery has been a treatment option for centuries, as we’ll discuss throughout this article. However, with the ever-increasing placement of dental implants, endodontic surgery may have seen a decrease in popularity. One must understand that failed endodontic therapy does not automatically need to lead to extraction and replacement, as surgical endodontic therapy properly performed has a very good and predictable prognosis. Also, today’s practitioners are extremely fortunate to have experienced the advent of technology such as the surgical microscope, microsurgical instruments, and cone beam commuted tomography.

Endodontic surgery has a very high success rate, especially when the practitioner has a thorough understanding of the cause of the failed treatment leading to surgery. As with all aspects of dentistry, understanding the etiology of the disease is the most predictable way of developing treatment for the offending disease. In 1884, Whitehouse wrote, “A few moments of consideration of the original cause of trouble at the apex of roots will enable us to realize what is required to be accomplished in the way of successful treatment. If the original cause is admitted being irritation from decomposing pulp, its removal will in most cases effect a cure.” (1) We will now present the historical context for multiple endodontic surgical procedures that are still performed today.

Intentional Replantation

While today, periradicular surgery is usually performed by clinicians who have made the correct decision to do so based on their understanding of disease etiology, this surgery was not always warranted when it was first performed centuries ago. The first recording of periradicular surgery goes back to the 11th century when Abulcasis described the first account of what is now referred to as an intentional replantation, or extraction replantation. (2) In order to maintain the tooth in the proper position, he used ligatures to splint the replanted tooth. (3)

Some early replantations were actually transplantations and were not performed due to the presence of disease, at least from the point of the donor participant. In 1787, Thomas Rowlandson produced an etching titled “Transplantation of Teeth,” which illustrated a luckless pauper having a tooth extracted to be placed in a member of aristocracy. (4)

Incision and Drainage (I & D)

Another early dental surgical procedure was the Incision and Drainage (I & D), which Lorenz Heister discusses extensively in his 1724 book entitled Lehrbuch der Chirugie. (3) Historically, the I & D was one of the most frequently performed procedures as well. It has been well-known for years that establishing drainage is a very important aspect of endodontic surgery. I & D procedures were often performed by individuals other than dentists and physicians if oral swellings became life-threatening. (5)

Root-End Resection (Apicoectomy)

When attempting to determine the exact historical facts, there frequently is some disagreement regarding who first performed the specific procedure. That again appears to be the case with root-end resection. In 1720, Savile discovered a skull in Ecuador with a tooth that was implanted and gave indications of resection of the apical portion of the root. (4) Fastlicht disproved Saville’s claim and felt the tooth was simply shaped differently at the apex. (5) There is significant documentation to support that this technique was used by Smith in 1871 for the first root-end resection of a tooth with a necrotic pulp and surrounding alveolar lesion. (5)

The first mention of tracing a “fistula” (what we now refer to as a sinus tract) and then performing a root-end resection was provided by Brophy in 1880. (6) Brophy reported what was referred to as a root-end resection with immediate root canal filling. (5, 6) This was later referred to by Mead and others as the post-resection filling technique. (5, 16) In addition to tracing the “fistula,” Brophy did some diagnostic procedures that are still used today, as he evaluated the tooth with heat as well as a test cavity. (5, 6) For heat testing, he heated a small round file and applied it to gold filings, while his test cavity was performed in the same manner that we perform them today. (5, 6)

Root Amputation

The first full root amputation was performed by Magitot in 1867 (7). Inspired by Magitot, in 1890, at the American Dental Association’s annual session, M. L. Rhein presented his paper “Amputation of roots as a radical cure in chronic alveolar abscess”. (5, 17) He described his treatment of filling the roots and excising the diseased portion after which he used a bur to remove the surrounding pathologic tissue. (5, 17) Frustrating to him, this did not seem to gain much traction as a popular technique despite the success he was able to achieve. (5, 17)

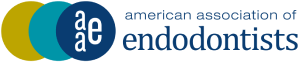

Shortly after Rhein presented his paper, however, an evolution in endodontic surgery began in the early 1900s. In 1908, Beal published an article on resection of a root called “Resection de l’Apex”. (8) Five years later, Bazant (from Czechoslovakia) published “Resection radices,” a paper with clear and detailed information on indications of root-end resection that became one of the most important publications in the eastern Europe sector. These developments led to additional significant and detailed publications. As one example, Faulhaber and Neumann provided an extensive description of their surgical armamentarium, anatomical considerations, and specific techniques. (10)

Figure 1 (Reprinted with permission from Surgical Endodontics by JL Gutmann and JW Harrison)

Flap Design

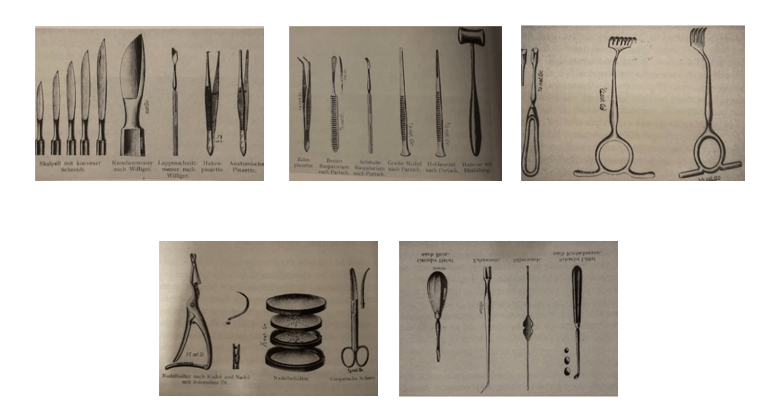

The surgeon must consider many variables when deciding what type of flap to use and where the incisions should be, as there are many different designs to choose from. While there has been an evolution of techniques through the years, the principles remain the same. One of the first thorough reviews of surgical flaps for endodontic surgery was conducted by Hofer from Vienna in his 1935 paper entitled “Wurzelspitzenresektion und Zystenoperationen.” (11)

Figure 2 (Reprinted with permission from Surgical Endodontics by JL Gutmann and JW Harrison)

Root-end Preparation

After resection, the root end is prepared using specialized instruments to remove a portion of the gutta-percha and create space for the root-end filling. One of the original root-end preparation techniques was described by Von Hipple in 1914, when he referred to vertical slot root-end preparation as “Slitmethoden,” which was indicated when post and core were present. (12) This preparation was modified by the addition of retentive grooves by Ruud in 1947. (18, 19) A few years earlier, in 1939, Tangerud designed the first handpiece to facilitate root-end preparation. (13, 18) This handpiece measured 2.5 mm high by 4 mm broad. (13, 18)

Over the last 30 years, many different shapes and sizes of ultrasonic tips have been developed to allow for a smaller osteotomy and root-end preparation to just about any apex. The size comparison of a regular operative handpiece, a handpiece designed for root-end preparation, and an ultrasonic tip designed specifically for root-end preparation is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3 (Reprinted with permission from Color Atlas of Microsurgery in Endodontics by S Kim, G Pecora, and R Rubinstein)

Root-end Fillings

Historically, several materials have been proposed for root-end fillings, including amalgam, reinforced zinc oxide and eugenol cements, gutta-percha, composite and epoxy resins, glass-ionomer, and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), and more recently introduced bioceramic root repair material. The ideal root-end filling material should be biocompatible, have an adequate apical seal, consistent handling properties, long-term clinical success, inhibit microorganism growth, and demonstrate dimensional stability. (15)

Endodontic Education

The classic view that endodontic surgery is a last resort is based on experience with accompanying unsuitable surgical instruments, inadequate vision, frequent postoperative complications, and failures that often resulted in extraction of the tooth. As a result, the surgical approach to endodontic therapy, or surgical endodontics, was taught with minimal enthusiasm at dental schools and was seldom used in private practice. Stated simply, endodontic surgery was not considered to be an important part of the endodontic education. Fortunately, this changed when the microscope, microsurgical instruments, and more biologically acceptable root-end filling materials were introduced in the mid-1990s. (14) See table 1 for a list of the differences between traditional and microsurgical approaches to endodontic treatment.

Table 1 Differences between traditional and microsurgical approaches

| 1. Osteotomy size | Traditional

Approx. 8–10 mm |

Microsurgery

3–4 mm |

| 2. Bevel angle degree | 45–65 degrees | 0–10 degrees |

| 3. Inspection of resected root surface | none | always |

| 4. Isthmus identification & treatment | impossible | always |

| 5. Root-end preparation | seldom inside canal | always within canal |

| 6. Root-end preparation instrument | bur | ultrasonic tips |

| 7. Root-end filling material | amalgam | MTA/bioceramic putty |

| 8. Sutures | 4 × 0 silk | 5 × 0, 6 × 0 monofilament |

| 9. Suture removal | 7 days post-op | 2–3 days post-op |

| 10. Healing Success (over 1 yr) | 40–90% | 85–96.8% |

| 11. Exposed dentinal tubules | Many exposed | Minimal amount exposed |

| 12. Buccal plate loss | Greater buccal plate loss | Minimal buccal loss |

| 13. Potential periodontal involvement | Minimal chance | Greater chance |

| 14. Possible lingual perforation | Minimal chance | Greater chance |

| 15. Identification of apices | Very easy | Potential to miss the lingual |

| 16. Elimination of accessory canals | Much greater chance | Much less chance |

The Future?!

With approximately 75% of the endodontic therapy in America being performed by general dentists, becoming proficient at retreatment (both nonsurgical and surgical) is extremely important to becoming a reliable and successful practitioner. Due to better techniques, instruments, and materials – in addition to a better understanding of wound-healing – endodontic surgery need not be considered only as a last resort. While endodontic surgery does not have a 100% success rate, neither do the alternatives of extraction and replacement, or any other dental procedure for that matter. While implant surgery is performed more frequently than endodontic surgery in both academic and private practice settings, there is no evidence to suggest that implants have better outcomes than properly performed nonsurgical or surgical endodontic therapy. (5, 20) With a high percentage of successful treatment results for both conventional endodontics and surgical endodontics, almost all teeth with endodontic lesions can be successfully treated.

Endodontic surgery should be viewed as a valued treatment option with a predictable prognosis. As we know, patients prefer saving their natural teeth whenever possible, and the benefits in doing so are more than just financial. Your natural teeth have many advantages over the prosthetic alternatives, including but not limited to cosmetics, emergence profile, contour, contact, occlusion, and reduced food impaction. If we continue to research this area and base our treatment on the science, the future looks bright for both the patient and the endodontist. Lastly, we feel it’s up to us as trained endodontists to educate general dentists and the public about the benefits of endodontic surgery.

Dr. James Gutmann

Once again, we would like to recognize Dr. James Gutmann as the most thorough endodontic historian of our time. We found his writings and presentations to be extremely valuable and educational in putting together this brief synopsis.

References

- Whitehouse W. Br J Dent Sci 1884; 27:238-240.

- Fauchard P. Le Chirurgien dentist outrait edes’dents. Paris: Chez Pierre-Jean Mariette 1746.

- Weinberger BW. Introduction to the History of Dentistry. St. Louis, The CV Mosby. Co., 1948;1:205

- Pindborg JJ, Marvitz L: The Dentist in Art. Chicago, Quadrangle Books, Inc., 1960.

- Gutmann JL, Gutmann MS: Historical Perspective on the Evolution of Surgical Procedures in Endodontics.

- Brophy TW. Caries of the superior maxilla. Chicago Med J Exam 1880; 41:582-586

- Carvalho-Silva E. Cirurgia em endodontia. In: DeDeus QD, ed. Endodontia, 3rd Rio de Janeiro: Editoria Medica e Cientifica Ltda., 1982: 505–549.

- Beal M. De Ia resection sw l’apex. Rev Stomatol (Paris) 1908; 15:439-446

- Bazant F. Resectio radicis. Zubni Lek 1913; 13:21-27

- Faulhaber B, Neumann R. Die chirugishce Behandlung der Wurzelhauterkrankungen. Berlin: Herman Meusser, 1912; 19

- Hofer O. Wurzelspitzenresektion und Zystenoperationen. Z Stomatol 1935; 32: 513-533

- Von Hippel R. Zur Technik der Granulomoperation. Dtsch Monatsschr Zaheilkd 1914; 32: 255-265

- Tangerud BJ. Den retrograde rotbehandling ved alveotomi. Nor Tannlaegeforen Tid 1939; 49: 170-175

- Syngcuk Kim. Modern Endodontic Surgery Concepts and Practice: A review JEndod.1999; 32: 601-623

- Benjamin Rencher. Comparison of the sealing ability of various bioceramic materials for enododntic surgery Restor Dent Endod. 2021 Aug;46(3): e35

- Mead SV. Oral Surgery. St. Louis: The CV Mosby Co., 1933; 560-572.

- Rhein ML. “Amputation of roots as a radical cure in chronic alveolar abscess.” Dental Cosmos. 1890; 32:904-905.

- Gutmann JL, Harrison JW. Surgical Endodontics. St. Louis, Tokyo. Ishiyaku EuroAmerica, Inc., 1994; 16-19.

- Ruud AF. Slitsmethoden ved retrograk rotfylling. Nor Tannlaegeforen Tid, 1950; 60:471-479.

- Hannahan JP, Eleazar PD. Comparison od Success of Implants versus Endodntically Treated Teeth. JEndod. 2008; 34:1302-1305.