The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) continues to advocate for fair and transparent insurance practices that support patient access to care and the sustainability of specialty practices. As part of this effort, AAE recently submitted comments in support of Massachusetts Senate Bill 704, legislation addressing the use of virtual credit cards by dental insurance providers.

Virtual credit card payments often impose processing fees that reduce reimbursement for care already delivered, creating unnecessary administrative costs for dental practices. In its comments to Massachusetts lawmakers, AAE emphasized that these practices can strain provider resources and discourage participation in insurance networks—ultimately limiting patient access to care.

AAE expressed strong support for provisions in S.704 that would prevent insurers from mandating credit cards as the sole method of reimbursement and require affirmative provider consent before credit card or virtual credit card payments are initiated. The legislation also promotes greater transparency by ensuring providers receive clear remittance information and advance disclosure of any associated fees.

Endodontists frequently provide urgent, specialized treatment for patients experiencing dental infections and pain. AAE noted that excessive administrative burdens and hidden payment fees can interfere with the timely delivery of this care. By allowing providers to choose their preferred payment method, S.704 helps protect practice sustainability while supporting efficient, patient-centered care.

AAE’s engagement on S.704 reflects its broader commitment to advocating for policies that reduce unnecessary administrative barriers, promote fairness in reimbursement, and strengthen the dental community. By supporting thoughtful reforms in Massachusetts, AAE continues to stand up for endodontists and the patients who rely on their specialized care.

The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) continues its strong advocacy for policies that support patient access to timely, high-quality care and protect the sustainability of specialty practices. As part of this effort, AAE recently submitted formal comments supporting Florida Senate Bill 1130, legislation aimed at improving insurance claims payment practices for health care providers.

SB 1130 addresses insurer practices that can undermine patient care, including inappropriate downcoding and delayed or unclear reimbursement decisions. In its comments to Florida lawmakers, AAE emphasized that these practices create unnecessary administrative burdens for providers and can interfere with patients’ ability to receive prompt, medically necessary treatment.

Endodontists routinely deliver urgent care for patients experiencing severe dental pain and infection—conditions that often require immediate intervention to prevent serious complications. AAE highlighted that SB 1130 would help preserve access to this care by establishing clearer restrictions on downcoding, increasing transparency when payment reductions occur, and strengthening prompt payment standards.

The legislation also promotes greater accountability in prior authorization and utilization review processes, including improved electronic systems and clearer standards for insurer decision-making. These reforms are designed to reduce treatment delays, enhance continuity of care, and ensure reimbursement aligns with the services provided.

AAE’s support for SB 1130 reflects its broader commitment to advocating for fair, transparent insurance practices that allow endodontists to focus on patient care rather than administrative obstacles. By engaging early with policymakers, AAE continues to champion legislation that strengthens specialty practices and protects access to essential dental care.

Following its strong opposition to earlier proposals that threatened to weaken specialty advertising standards in Wisconsin, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) welcomed recent action by the Wisconsin Dentistry Examining Board to clarify and strengthen its dental specialty advertising rules. The Board’s proposed revisions to Chapter DE 6 represent a meaningful step toward protecting patients from misleading claims while reinforcing the value of accredited specialty education.

In formal comments submitted to the Board, the AAE expressed support for provisions that clearly define what constitutes false, misleading, or deceptive advertising. By providing greater specificity and transparency, the proposed rules help ensure consistency in enforcement and offer clearer guidance to dentists seeking to comply with advertising requirements. Most importantly, these safeguards enhance consumer protection and support informed decision-making by patients.

The AAE also commended the Board for reinforcing the principle that the title “specialist” must be reserved for dentists who have completed a postdoctoral educational training program accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA). Requiring dentists who are not specialists to clearly identify themselves as general dentists is a critical protection against patient confusion and aligns with public expectations regarding specialty credentials.

At the same time, the Association raised concerns about the continued use of alternative titles—such as “implantologist”—that may function as a proxy for specialty designation. While the proposed rules require disclaimers identifying these providers as general dentists, the AAE cautioned that such distinctions may not be readily understood by patients. From a consumer perspective, alternate terminology can still imply a level of specialty expertise that does not reflect CODA-accredited training. The AAE encouraged the Board to further strengthen the rule by limiting advertising titles to prevent unintended confusion.

Finally, the AAE strongly supported provisions preventing a dentist from implying that all practitioners within a group practice are specialists unless each individual has earned that designation. This clarification is essential to preserving the integrity of specialty recognition and ensuring that patients receive accurate information when choosing their provider.

Together, these proposed revisions reflect a shared commitment to truth in advertising, patient protection, and professional accountability. The AAE’s engagement in Wisconsin underscores its continued advocacy for clear, enforceable standards that uphold the value of accredited specialty education and protect the public trust. By supporting thoughtful regulatory improvements, the Association continues to safeguard your ability to practice as a recognized specialist.

As the 2026 legislative cycle kicks off, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) is already actively engaging with policymakers to strengthen the dental community and expand access to high-quality oral health care. AAE recently submitted a series of comment letters supporting state legislation to ratify the Dentist and Dental Hygienist Interstate Compact, underscoring the Association’s continued commitment to effective, collaborative advocacy.

To date, AAE has expressed support for compact legislation introduced in Arizona, Missouri, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New Mexico and Oklahoma. These early advocacy efforts highlight AAE’s proactive approach to shaping policy that supports a strong, mobile dental workforce and benefits patients across the country.

In its communications with lawmakers, AAE emphasized that interstate licensure compacts help address workforce shortages—particularly in rural and underserved areas—while maintaining rigorous licensure and public safety standards. By reducing unnecessary administrative barriers, the compact allows qualified dentists and dental hygienists to practice where they are needed most, strengthening collaboration and continuity of care throughout the dental community.

AAE also noted that the compact promotes accountability and public trust through background checks, coordinated disciplinary data sharing, and consistent licensure requirements across participating states. These safeguards ensure that workforce flexibility enhances, rather than compromises, patient protection.

As the specialty organization representing more than 8,000 endodontists worldwide, AAE continues to advocate for policies that recognize the essential role of dental specialists in preserving natural teeth, managing dental pain, and supporting comprehensive oral health care. Supporting interstate compact legislation aligns with AAE’s broader mission to strengthen the dental workforce and the dental community as a whole.

AAE will continue to closely monitor additional interstate compact bills introduced during the 2026 legislative cycle and will support legislation that advances patient access, protects public safety, and strengthens the dental profession. Through sustained engagement with lawmakers and coalition partners, AAE remains committed to advancing policies that benefit endodontists, the broader dental community, and the patients they serve.

The Minnesota Board of Dentistry is considering proposed revisions to state regulations that would expand the scope of practice for dental therapists. These changes represent a significant shift in Minnesota’s long-standing regulatory framework governing the delivery of dental care. If adopted, the proposal would blur established professional roles, weaken accountability, and raise serious concerns about patient safety and standards of care.

In response, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) submitted formal opposition to the Board, emphasizing that scope-of-practice decisions must align with a provider’s education, training, and level of clinical responsibility. Endodontists complete rigorous, Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA)–accredited postdoctoral education to ensure competence in diagnosing and managing complex disease. Expanding dental therapists’ authority beyond their intended supportive role risks delegating critical clinical responsibilities to practitioners who are not trained to assume them independently.

The AAE also underscored that this issue extends beyond access to care. While improving access is an important policy objective, it cannot come at the expense of safety, quality, or professional standards. Expanding scope of practice by redefining core clinical responsibilities sets a dangerous precedent and undermines the dentist-led model of care that has long protected patients. Dental therapists play an important role on the oral health care team, but that role is designed to complement, not replace, dentist oversight and accountability.

Additionally, expanding scope of practice risks creating confusion for patients about provider qualifications and responsibility for care. When regulatory lines are blurred, patients may reasonably assume that all providers are equally trained to deliver the same level of care. This confusion erodes public trust in the dental care delivery system and conflicts with the Board’s fundamental responsibility to protect public health.

The AAE urged the Minnesota Board of Dentistry to reject the proposed scope-of-practice expansion and to maintain existing regulatory definitions that appropriately reflect education, training, and professional responsibility. The Association also called for additional stakeholder engagement, including meaningful dialogue with dental specialty organizations, before advancing any further changes.

Through consistent, evidence-based advocacy, the AAE continues to stand firm against regulatory efforts that threaten patient safety and professional standards. Our engagement in Minnesota reflects the Association’s ongoing commitment to protecting the integrity of dental specialties—and to supporting endodontists as they provide high-quality, specialist-level care to patients every day.

By Christine I. Peters, DMD; Bettina Basrani, DMD, MS, PhD; and Ove A. Peters, DMD, MS, PhD

Almost every clinician who performs root canal therapy has lived some dreadful moment leading to a halt of treatment: something does not look and feel right or behaves incorrectly. Anatomy surprises us, the root canal is not to be found or is tight and the instrument suddenly looks shorter. Perhaps there is unexpected bleeding. Abrupt pain could be experienced during treatment. The patient returns the next day with a swelling, or worse, with a story that begins, “Ever since you treated me yesterday, my face feels different.”

Endodontic treatment follows a structured sequence: diagnosis, access, cleaning, shaping, and obturation—but biology rarely adheres strictly to protocol. Patients bring complex medical, dental, and emotional histories that influence outcomes in ways we cannot always foresee.

We hope mishaps never occur, but the reality is that procedural errors and complications are an inherent part of endodontic practice. Entire textbooks1 have been devoted to endodontic mishaps because, statistically, they can happen to every clinician over a long enough timeline. What matters most is not whether errors occur, but how we recognize them, respond to them, and prevent them from happening again.

At the 2025 AAE Annual Meeting in Boston, our session “What Happens When Everything Goes Wrong?? Errors and Complications in Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatments—And How to Make It Right” gave us an opportunity to explore serious, sometimes surprising events that can occur during routine procedures. We explored a broad spectrum of complications ranging from misdiagnosis and non-healing lesions to access errors, irrigation accidents, subcutaneous emphysema, file separation, and unusual anatomical variations. Some of these events are rare; others are preventable missteps that can occur particularly when we are rushed, fatigued, or working in anatomically challenging situations.

In this Communiqué contribution, we expand on two consequential classes of complications: irrigation-related accidents and shaping-related mishaps. Clinicians consistently identify root canal treatments as stressful2: They share common themes: anatomical complexity, loss of control at a critical moment, and the importance of deliberate decision-making once a problem arises.

Our goal is to provide practical guidance and pragmatic prevention advice, so that when complications occur, clinicians have both a systematic approach for managing them and the confidence to make the right decisions for their patients: clinically, ethically, and emotionally.

As we emphasized at the AAE Meeting in Boston, mistakes happen and are not the end of the road. They are opportunities for reflection and refinement. When clinicians understand not only what went wrong, but why, our profession as a whole becomes safer and stronger.

Irrigation Mishaps: When Chemistry Meets Anatomy

Among all endodontic complications, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) accidents evoke perhaps the strongest emotional response. They are sudden, dramatic, and unsettling for both patient and clinician. A routine appointment can change within seconds into an acute event marked by severe pain, rapid swelling, and soft-tissue discoloration that may evolve over hours or days.

Although these accidents are often perceived as unpredictable, clinical experience and published data reveal consistent patterns3. Most NaOCl injuries occur in the maxilla, particularly in molars where buccal cortical bone may be thin or fenestrated. Female patients appear disproportionately represented, likely reflecting anatomical differences in bone and soft-tissue thickness. In a significant subset of cases, an unrecognized perforation, resorptive defect, open apex or bone fenestration creates a pathway for irrigant extrusion even when technique is otherwise careful.

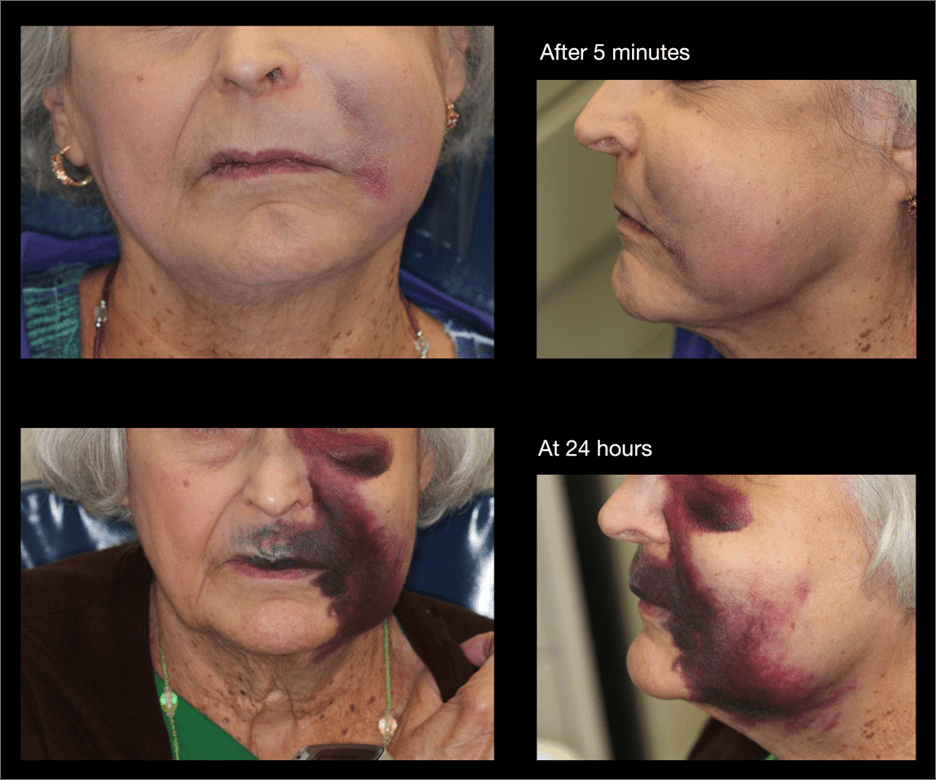

Anatomy alone, however, does not cause a sodium hypochlorite accident. Most events result from positive pressure irrigation combined with momentary needle wedging or overly deep placement. When coronal escape of irrigant is blocked, solution follows the path of least resistance into periapical or soft tissues. The clinical presentation, immediate sharp pain during irrigation, profuse bleeding, rapidly expanding swelling, and ecchymosis, is distinct and should not be mistaken for a routine postoperative flare-up. (Fig. 1)

When an irrigation accident occurs, the clinician’s response matters enormously4. Immediate cessation of treatment and clear, calm communication are essential. Gentle irrigation with saline helps dilute residual NaOCl. Cold compresses in the initial phase, appropriate analgesia, and selective use of corticosteroids help manage inflammation and pain. Antibiotics are indicated when mucosal integrity is compromised or infection risk is elevated. Close follow-up, particularly during the first 24 to 48 hours, is critical, and advanced imaging or medical collaboration may be necessary when swelling threatens deeper fascial spaces.

Despite the alarming early presentation, outcomes are generally favorable. With structured supportive care, most patients recover fully, even after severe tissue reactions. In many cases, the long-term impact of the event depends less on the injury itself than on how it is managed and communicated.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Safe irrigation requires respect for anatomy and constant control: avoiding needle binding, maintaining distance from the working length, ensuring visible irrigant backflow, and using side-vented needles with gentle pressure. Adequate canal preparation before irrigation is essential. When risk factors such as large lesions, immature apices, or suspected fenestrations are present, modifying the irrigation strategy, or using negative-pressure systems, can significantly reduce risk. While NaOCl accidents cannot be entirely eliminated, thoughtful technique and anatomical awareness make them exceedingly uncommon.

Shaping Mishaps: When Instruments Meet Reality

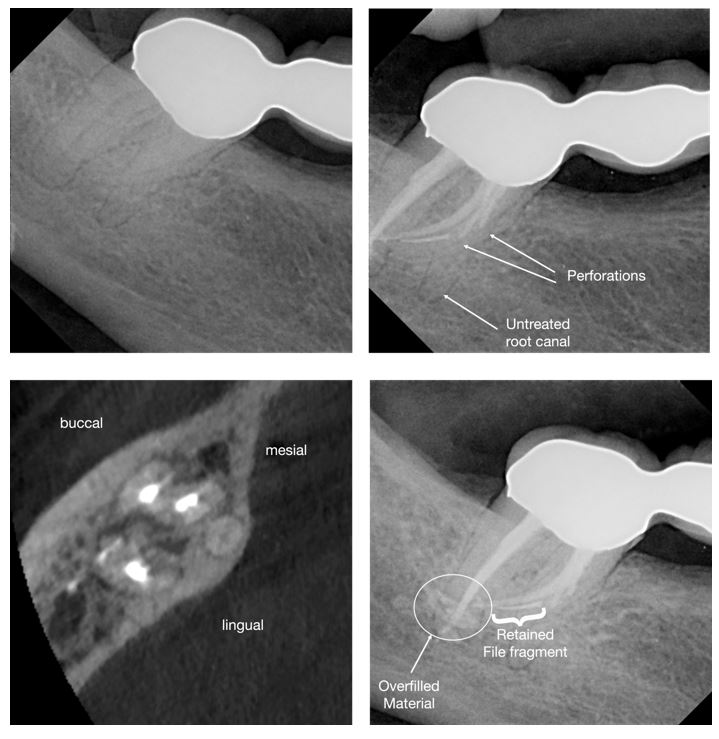

Shaping complications tend to develop more quietly than irrigation accidents. They often begin with subtle warning signs: a file that catches unexpectedly, loss of tactile feedback, or a slight deviation noticed on a radiograph. If not recognized early, these small deviations can progress to ledges, transportation, perforations, or instrument separation.

Many shaping mishaps originate during assessment. Two-dimensional radiographs, while indispensable, cannot fully represent three-dimensional root canal anatomy. Severe curvatures, apical bifurcations, S-shaped canals, and unusual molar or premolar configurations are easily underestimated. Small field-of-view CBCT has proven invaluable in complex posterior cases and can meaningfully alter treatment planning before irreversible steps are taken. (Fig. 2)

Insufficient glide-path preparation remains another major contributor. Contemporary nickel–titanium systems are remarkably capable, but they cannot compensate for a canal that lacks a smooth, reproducible pathway5. Without an adequate glide path, rotary or reciprocating instruments are subjected to increased torsional and cyclic stresses. In addition to classic torsional failure and cyclic fatigue, emerging evidence highlights torsional fatigue as a combined failure mechanism affecting modern instruments.

Instrument fracture remains one of the most anxiety-provoking events in endodontic practice. Yet presence of a retained instrument fragment itself is not synonymous with failure6. The prognosis depends heavily on fragment location, canal anatomy, remaining tooth structure, and the quality of disinfection achieved prior to separation. Aggressive retrieval attempts, particularly without magnification or appropriate training, can convert a manageable complication into perforation, root fracture, or tooth loss.

When a file fractures, the most important immediate step is restraint. Clinicians must review anatomy and obtain additional imaging when necessary. The next step is to evaluate whether retrieval, bypassing, retention, or referral is most appropriate preserves both the tooth and the clinician’s judgment. Transparent communication with the patient is essential. Referral, when warranted, reflects professionalism rather than inadequacy.

Preventing shaping mishaps relies on respect for anatomy, for instruments, and for one’s own limits. Establishing a reliable glide path, allowing files to cut without force, maintaining lubrication and irrigation, and limiting instrument reuse are all critical. Single-use protocols remain the safest option in challenging anatomy. Knowing when not to proceed is a hallmark of clinical maturity.

The Path Forward

Endodontic complications are never welcome, but they are powerful teachers. They remind us that dentistry is not merely a technical sequence, but a dynamic interaction between biology, judgment, and human responsibility. Excellence is not defined by the absence of errors, but by the ability to recognize them early, respond thoughtfully, and recover in a way that prioritizes patient safety and trust.

Clinicians may focus on procedural errors such as the ones described here while not considering other unfavorable outcomes such as life-threatening infections7 or even not recognizing a neoplasm. Irrespective, when we think that everything goes wrong, the most important action may be the simplest: pause, reassess, and proceed deliberately. Complications are not the end of the road, they are opportunities to refine judgment, deepen understanding, and deliver better care for our patients.

References

1 Torabinejad M, Sabeti M (eds). Management of Endodontic Complications. 1st edn, 2023, Quintessence, Batavia, IL, USA

2 Dahlström L, Lindwall O, Rystedt H, Reit C. ‘Working in the dark’: Swedish general dental practitioners on the complexity of root canal treatment. Int Endod J 2017;50:636-645

3 Cho-Kee D, Basrani BR, Vera J, Ordinola-Zapata R, Aguilar RR. Sodium Hypochlorite Accidents: A Retrospective Case-series Analysis of CBCT Imaging and Clinician Surveys. J Endod 2025 51:1485-1489.

4 Farook SA, Shah V, Lenouvel D, Sheikh O, Sadiq Z, Cascarini L, Webb R. Guidelines for management of sodium hypochlorite extrusion injuries. Br Dent J 2014;217:679-84.

5 Plotino G, Nagendrababu V, Bukiet F, Grande NM, Veettil SK, De-Deus G, Aly Ahmed HM. Influence of Negotiation, Glide Path, and Preflaring Procedures on Root Canal Shaping-Terminology, Basic Concepts, and a Systematic Review. J Endod 2020;46:707-729.

6 Parashos P, Messer HH. Rotary NiTi instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod 2006;32:1031-43.

7 Shemesh A, Yitzhak A, Ben Itzhak J, Azizi H, Solomonov M. Ludwig Angina after First Aid Treatment: Possible Etiologies and Prevention-Case Report. J Endod 2019;45:79-82.

Figure 1: Clinical impression of a sodium hypochlorite accident. Photographs show the dramatic progression in the first 24 hours.

(Case courtesy Dr. Ray)

Figure 2: Clinical example of a mandibular second molar with unusual anatomy. Postoperative radiographs show the presence of a retained instrument fragment along with further procedural errors.

The AAE Constitution and Bylaws Committee presents proposed revisions to the Constitution and Bylaws of the American Association of Endodontists. These proposed revisions have undergone review by the committee, AAE Legal Counsel, and the AAE Board of Directors. The General Assembly will vote on these proposed changes at its meeting on April 17, 2026 in Salt Lake City.

The proposed changes are summarized below.

Educator Member Proposed Changes

The Constitution and Bylaws Committee considered proposed amendments to the AAE Educator Membership category, brought forward by the Membership Engagement Committee, the Educational Affairs Committee, and the AAE Board. The amendments provide for an expansion of Educator membership eligibility to include internationally trained endodontists who hold full-time faculty positions in CODA-accredited programs in an effort to recognize their academic contributions to the specialty. The proposed revision would enable these members to serve on AAE committees and receive some of the access and benefits of Educator membership while maintaining existing limitations regarding voting privileges and eligibility for officer positions.

Foundation for Endodontics Proposed Changes

The Foundation for Endodontics has undertaken a multi-year effort to modernize its governance and update its governing documents. Several of the Foundation’s governance updates necessitate corresponding changes to AAE governing documents. The AAE Board has reviewed and approved these changes, including removal of the requirement in the Foundation’s bylaws that the Foundation’s changes to its own bylaws undergo AAE Board review and approval, except when changes directly impact the AAE Bylaws.

Key updates which require changes to the AAE Bylaws, and thus, approval by the General Assembly, include:

- Removing the Foundation mission statement from AAE bylaws to avoid future misalignment, while retaining it within the Foundation’s own governing documents.

- Updating Board of Trustees composition to reflect a new proposed structure.

- Revising term-length references to align with the Foundation’s new trustee and officer service structure.

- Updating language regarding nomination, election and approval processes for Foundation trustees and officers by the AAE General Assembly.

Constitution Amendment Process

The Constitution and Bylaws Committee proposes suggested revisions to article XII of the AAE Constitution intended to clarify the process by which constitutional amendments may be proposed. This issue arose during recent governance work, when questions emerged regarding how amendments are properly initiated and transmitted for consideration.

Compiled by Dr. Austyn Grissom

Compiled by Dr. Austyn Grissom

Dr. Stephanie Sawyer is in her second year of endodontics residency at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In this Resident Spotlight, Dr. Sawyer shares more with us about her journey to endodontics, her commitment to personal wellness, and what is on the horizon for her future after residency.

The Paper Point: Thanks for taking time to chat, Dr. Sawyer. Let’s start by telling everyone a little bit about yourself.

Dr. Sawyer: I’m currently a second-year endodontic resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. I’m originally from Long Island, New York, but Alabama has truly become a second home over the past several years. Outside of dentistry, I love staying active, trying new restaurants, traveling, and cooking with my husband—who is a prosthodontist. I’m very passionate about maintaining balance between my professional goals and personal wellness, which has been especially important during residency.

The Paper Point: What first sparked your interest in becoming a dentist, and later, endodontist?

Dr. Sawyer: My interest in dentistry started with my appreciation for the combination of medicine, problem-solving, and hands-on procedures. As I progressed through dental school and later through my AEGD and time in private practice, I found myself drawn to complex cases and diagnosing the “why” behind a patient’s pain. Endodontics stood out because it blends critical thinking, precision, and the ability to provide immediate relief to patients who are often in significant discomfort. That ability to make a meaningful impact in a short amount of time ultimately solidified my decision to pursue endodontics.

The Paper Point: For any of our readers in dental school who are on the fence between practicing after graduation versus pursuing endo residency right out of school: how did that time you spent in your AEGD and then private practice as a general dentist influence the way that you approach life as an endodontic resident?

Dr. Sawyer: Spending time in an AEGD and then in private practice was incredibly valuable for me. It helped me build confidence, efficiency, and strong communication skills before entering residency. I gained a deeper understanding of what general dentists need from specialists, which has really shaped how I approach referrals and case planning. It also gave me perspective—I came into residency more focused, intentional, and appreciative of the opportunity to specialize. I truly believe that those experiences made me a better resident and will ultimately make me a better endodontist.

The Paper Point: Will you be presenting any of your research at AAE26 in Salt Lake City?

Dr. Sawyer: Yes, I will be presenting at AAE26 in Salt Lake City. During residency, I have been primarily involved in one main research project evaluating the antimicrobial properties of oregano oil. While we are still awaiting the finalized qPCR data for that study, I will be presenting a table clinic focused on the relationship between medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) and endodontic procedures, including both surgical and nonsurgical treatment considerations. I’m looking forward to discussing clinical decision-making, risk assessment, and how endodontic therapy can play an important role in the management of these complex patients.

The Paper Point: I know that you are very intentional about your fitness and wellness routine even during this busy season. Tell us about what you do to stay active, and any tips you might have for the rest of us who are already slacking off our New Years Resolutions?

Dr. Sawyer: Staying active is a big priority for me, especially during stressful seasons. I try to keep things realistic and flexible—whether that’s a spin class, a run, a walk, a hike, or a quick HIIT workout. My biggest tip is not aiming for perfection. Even 20–30 minutes counts. I also remind myself that movement is something I get to do, not something I have to do. Giving yourself grace and building consistency over intensity makes a huge difference long term.

The Paper Point: One of the things that I miss most about Birmingham, AL is the food scene! If someone reading this happens to be passing through Birmingham, AL for the day- give us a recommendation for: a place to grab breakfast, a lunch spot, and your favorite dinner restaurant.

Dr. Sawyer: Birmingham truly has an amazing food scene and is one of the things I’ll miss most. For breakfast, you can’t go wrong with Hero Doughnuts or O’Henry’s. For lunch, I love Real and Rosemary or El Barrio—both are must-stops and never disappoint. Dinner is where Birmingham really shines, and some of my absolute favorites are Helen, Galley and Garden, and Current Charcoal Grill. And to finish the night, the cocktail scene is just as good—Key Circle Commons and Adios are hands-down my favorite spots.

The Paper Point: When you and your husband cook together, do you guys have a favorite dish that you make?

Dr. Sawyer: We love cooking together and enjoy experimenting with all different kinds of cuisine—from Mediterranean dishes to Thai food. One of our absolute favorites to make at home is Jet Tila’s green curry. It’s a recipe we keep coming back to and always feels like a fun night in the kitchen together.

The Paper Point: Once you complete your residency training this June, what’s next for you?

Dr. Sawyer: After graduation, my husband and I are planning a trip to Northern Italy to celebrate the completion of residency and this chapter of our lives. Following that, we’ll be relocating to the DMV area, where I’ll be joining a prosthodontic and endodontic specialty practice, Prostho.Endo.Dental Group. It’s a unique opportunity to work alongside a husband-and-wife prosthodontic/endodontic team, which makes it especially exciting for both of us.

The Paper Point: That’s awesome! You both deserve an amazing trip to celebrate each of your accomplishments, and I know that y’all are going to have a great time in Italy. Before we part, what is one piece of advice or motivational quote that has inspired you to keep going on the tough days?

Dr. Sawyer: One quote that has always stuck with me is: “You don’t have to be perfect—you just have to keep going.” Residency can be challenging, but remembering why you started and trusting the process makes all the difference.

Dr. Austyn Grissom is former chair of the AAE’s Resident and New Practitioner Committee.

There is something special about January, the quiet pause between what was and what is possible. The new year doesn’t require perfection. It doesn’t demand that we have everything figured out. Instead, it offers something much more powerful: the chance to begin again. As we step into a new year, I find myself reflecting on what fresh beginnings truly mean. Even after busy seasons and full calendars, we are always allowed to start again; with intention, with hope, and with purpose.

There is something special about January, the quiet pause between what was and what is possible. The new year doesn’t require perfection. It doesn’t demand that we have everything figured out. Instead, it offers something much more powerful: the chance to begin again. As we step into a new year, I find myself reflecting on what fresh beginnings truly mean. Even after busy seasons and full calendars, we are always allowed to start again; with intention, with hope, and with purpose.

In many ways, that same spirit mirrors the heart of our work and our profession. Endodontics is founded on restoration, renewal, and second chances; on helping patients preserve what matters most and rediscover comfort, confidence, and hope. It is truly a privilege to do work that, quite literally, offers people the opportunity for a new beginning.

This year, my goal is to keep our collective momentum moving in the right direction: forward. Forward in excellence. Forward in connection. Forward in leadership. Whether you are a resident, a new practitioner, or someone who has been engaged with the AAE for years, my hope is that 2026 becomes a year in which every member feels seen, supported, and inspired to contribute.

With the new year underway, I wanted to share a few important updates and reminders:.

One major milestone on the horizon is AAE26, taking place April 15–18, 2026, in Salt Lake City, Utah. There is truly nothing like being together in person at the annual meeting; learning, reconnecting, exchanging ideas, and surrounding ourselves with colleagues who challenge us to be better. If you haven’t registered yet, I encourage you to do so soon and begin planning your travel and accommodations early. These moments of connection are invaluable.

And last, but certainly not least, please mark your calendars for APICES 2026, happening August 14–15 in St. Louis. APICES continues to be one of the most meaningful experiences for residents and new practitioners as you navigate the transition from residency to the realities of practice. The RNPC is already working on an engaging and impactful program, and we cannot wait to see you all there. Registration will open June 2026.

I want to acknowledge that every new year brings different realities for each of us. Some are entering a season of growth. Some are navigating uncertainty. Some are building practices, managing families, overcoming personal hardship, or simply trying to keep all the plates spinning. Wherever you are, I want you to know: you belong here. And we are stronger together. Endodontics is a specialty defined by precision, patience, and resilience. Every day, we solve problems, relieve pain, and restore confidence. That work matters, and so does the way we support one another while doing it.

As we turn the page into 2026, I encourage you to lean in. Share your story. Submit an article. Ask questions. Build relationships. This organization is not just something you belong to, it is something that can shape you, support you, and help you grow.

If you have an idea you’d like the RNPC to bring to life, questions about the transition from residency to the “real world,” want to learn more about getting involved with the AAE, or are ready to submit an article for the next edition of The Paper Point, please feel free to reach out anytime at PCarpenter.DDS@gmail.com. I would love to hear from you.

Warmly,

Priscilla L. Carpenter, D.D.S., M.S.

Resident and New Practitioner Committee Chair

Endodontics is hard work, both physically and mentally. I’m not complaining, just stating facts. Anyone who has spent some time in the “trenches” practicing clinical endodontics can attest. The other evening as I was pondering my day, I felt especially tired. The reality was I didn’t really do anything different than the previous days. What was different was I had a number of patients questioning the scientific validity of what we do. We’ve all heard it: “Root canals cause cancer, root canals lead to other diseases, how can you leave a dead organ in the body”. My problem, I realized was not that I was any more physically tired than the day before, I was however mentally taxed! As clinicians, we’ve always had to correct patient misunderstandings, misconceptions and mistruths but over the past decade and especially the last couple of years we’ve entered a new era, one in which misinformation isn’t merely occasional, it’s systemic. What patients see on TikTok, hear from influencers, or read in online forums now competes directly with our training and expertise. Instagram is the new Dr. Google where once upon a time we were “bothered”, occasionally, by a patient that looked something up online. The consequences are no longer limited to chair-side confusion-they affect treatment decisions, access to care, public trust, and even governmental policy.

Endodontics is hard work, both physically and mentally. I’m not complaining, just stating facts. Anyone who has spent some time in the “trenches” practicing clinical endodontics can attest. The other evening as I was pondering my day, I felt especially tired. The reality was I didn’t really do anything different than the previous days. What was different was I had a number of patients questioning the scientific validity of what we do. We’ve all heard it: “Root canals cause cancer, root canals lead to other diseases, how can you leave a dead organ in the body”. My problem, I realized was not that I was any more physically tired than the day before, I was however mentally taxed! As clinicians, we’ve always had to correct patient misunderstandings, misconceptions and mistruths but over the past decade and especially the last couple of years we’ve entered a new era, one in which misinformation isn’t merely occasional, it’s systemic. What patients see on TikTok, hear from influencers, or read in online forums now competes directly with our training and expertise. Instagram is the new Dr. Google where once upon a time we were “bothered”, occasionally, by a patient that looked something up online. The consequences are no longer limited to chair-side confusion-they affect treatment decisions, access to care, public trust, and even governmental policy.