The Intersection Between Endodontic and Neuropathic Pain

By Brooke Blicher, DMD, and Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD

Introduction

Endodontists frequently meet patients on their worst days, marked by severe pain. Not all orofacial pain is equivalent, and not all orofacial pain is of odontogenic origin. As a result, patients with suspected non-odontogenic orofacial pain may present to endodontic practices. For these and all patients, a comprehensive diagnostic approach is of the utmost importance. Patients must be informed in realistic terms both of their diagnosis, including a differential diagnosis, and the expected prognosis of any proposed treatment. They should additionally be made aware of limitations to treatment modalities, and be given reasonable expectations for pain relief following such treatment. Thoughtful discussions on intraoperative and postoperative pain management should include consultation with managing medical parties when necessary.

Diagnosis drives appropriate treatment. For patients with non-odontogenic pain, endodontic therapies represent inappropriate care. That said, clinicians must be mindful of the fact that some patients with endodontic pathology can present with symptoms that present similarly to non-odontogenic pain. The following two cases exhibit patients presenting with inordinate levels of pain with a circuitous path to a definitive endodontic diagnosis. Management involved comprehensive diagnosis, informed consent and definitive endodontic treatment, with resultant successful pain management.

Case 1: Jennifer

Jennifer awoke three days prior to presenting in our Endodontics practice with pain described as “agonizing, dull, and constant” localized to her left mandible, but notably absent in the dentition. Ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and an expired opioid did not alleviate her symptoms. Lacking overt dental pain, Jennifer consulted her primary care physician, who suspected trigeminal neuralgia as the likely source of pain. Carbamazepine was prescribed and an MRI was ordered to rule out central lesions.

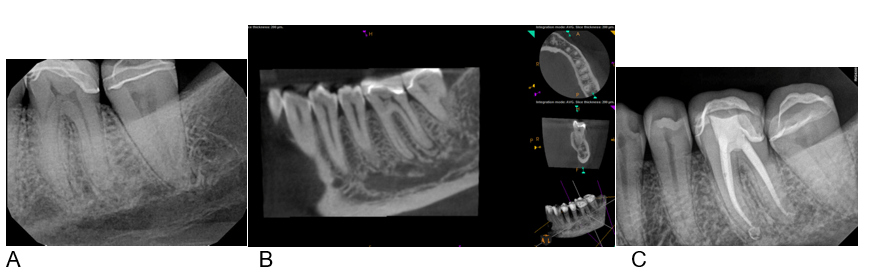

In the interim, her physician recommended a dental consultation to rule out odontogenic sources of pain. Jennifer’s general dentist noted no clinical or radiographic pathology on periapical radiograph (figure 1A). Due to the severity of reported symptoms, a referral was made to our Endodontics practice for a more detailed examination along with CBCT imaging. Jennifer’s comprehensive history on presentation included no relief of symptoms with carbamazepine. Additionally, she reported a history of cold sensitivity following crown placement on tooth #19 two years prior. Periapical testing revealed palpation tenderness on the left mandible and percussion tenderness of the left mandibular teeth, with more pronounced percussion tenderness on tooth #19. Pulp sensitivity testing revealed that while control teeth responded normally to both cold and heat, tooth #19 failed to respond to cold. Heat, however, caused pain consistent with her chief complaint. CBCT imaging (figure 1B) revealed periapical pathology localized to tooth #19.

An endodontic diagnosis of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis was made for tooth #19. Nonsurgical root canal therapy was recommended. That said, Jennifer’s reported pain intensity was greater than that typically reported for her diagnosis, and the lack of a response to combination therapy with ibuprofen and acetaminophen was atypical. Resultantly, suspicions were raised regarding a comorbid neuropathic pain diagnosis. Informed consent conversations included the potential for persistent neuropathic symptoms following definitive treatment of tooth #19. Additionally, as neuropathic pain can be exacerbated by nonsurgical and surgical dental treatment, Jennifer was informed of the possibility of worsening pain following endodontic treatment. Consultation with her physician regarding her diagnosis resulted in the continuation of her carbamazepine prescription during her postoperative period to mitigate any potential neuropathic pain symptom exacerbation by endodontic treatment.

Jennifer’s story does, thankfully, have a happy ending. Immediately upon delivery of procedural local anesthetic via inferior alveolar nerve block, Jennifer’s pain abated. Bupivacaine was used as part of the local anesthesia protocol because of its association with reduced postsurgical pain (Gordon et al) since patients with greater levels of preoperative pain tend to have greater postoperative pain. (Mattscheck et al) Nonsurgical root canal therapy was completed without complication, (figure 1C), and though Jennifer reported some soreness in her jaw and tooth for a few days following treatment, the pain of her chief complaint did not return. Jennifer’s physician tapered her carbamazepine prescription without issue.

Figure 1. Jennifer’s periapical image (A) did not showcase the periapical pathology evident in CBCT imaging (B) of tooth #19. Nonsurgical root canal therapy provided definitive pain relief. (C)

Case 2: Sandra

Sandra presented to our Endodontics practice to evaluate severe right sided facial and jaw pain. She reported a years-long history of right-sided migraines, along with longstanding cold sensitivity in her maxillary and mandibular right teeth. More recently, she developed pain described as a 10/10 intensity characterized by radiating discomfort, burning pain, and palpation tenderness in the right maxilla and mandible. Sandra’s pain was nonresponsive to combination therapy with ibuprofen and acetaminophen, nor her migraine preventive or abortive triptan therapy.

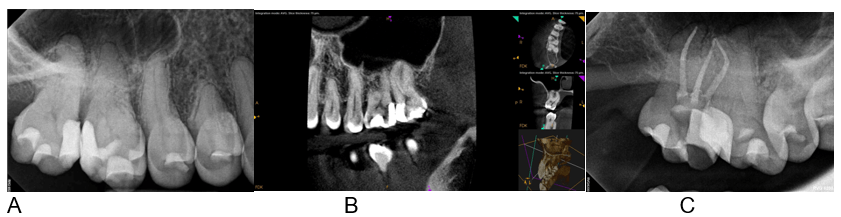

Clinically, palpation tenderness was noted across the right zygoma and right mandible. Clinical testing revealed percussion tenderness localized to tooth #2. Tooth #2 was additionally nonresponsive to cold, whereas all other teeth in the upper and lower right quadrants responded normally. An intact mesio-occlusal composite restoration was noted on tooth #2, and her periodontal exam was unremarkable. Periapical and CBCT imaging revealed deep restorative material proximal to the pulp as well as apical PDL widening localized to #2. (Figure 2A and B)

The endodontic diagnosis for tooth #2 was pulpal necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis. Nonsurgical root canal therapy was recommended. The reported burning quality of her extraoral symptoms, however, was inconsistent with odontogenic pain and suggested the development of neuropathic pain. The supposition of neuropathic pain was all the more reasonable given Sandra’s history of severe migraine headaches. Informed consent for endodontic treatment included a discussion of the potential persistence or exacerbation of burning symptoms and migraine headaches following endodontic intervention.

Nonsurgical root canal therapy was completed following a similar protocol as Jennifer above. (figure 2C) Bupivacaine was utilized as part of pretreatment local anesthesia given the high intensity of Sandra’s preoperative pain and its ability to mitigate postoperative pain. Sandra’s headache and pain providers were informed of the diagnosis and treatment plan and advised of the likely need for additional follow up.

These informed consent conversations, though, proved for naught. Sandra’s symptoms resolved entirely following endodontic treatment. Local anesthetic administration led to immediate relief of both burning and radiating pain, and definitive nonsurgical root canal therapy was completed without recurrence of pain. A follow up phone call one month later revealed that Sandra’s dental pain, burning facial pain and migraine headaches had not recurred. Though she remained on her migraine preventive medications, her quality of life dramatically improved.

Figure 2. Sandra’s preoperative periapical (A) and CBCT imaging (B) revealed deep prior restorative care proximal to pulp tissues as well as apical PDL widening localized to tooth #2. Nonsurgical root canal therapy provided definitive relief of symptoms.

Discussion

Both Jennifer and Sandra’s cases involved presumed central sources of pain. However, astute referrals coupled with patient perseverance landed these patients very appropriately in the dental sphere. Comprehensive diagnostics revealed endodontic pathology as at least contributors to symptoms. The confirmation of a dental source of pain was furthered by the use of local anesthetics to relieve symptoms along with nonsurgical root canal therapy. The quality of these patients’ lives were dramatically improved by the diagnosis of their true source of pain and their access to such diagnostic and treatment modalities.

That said, these cases are not always so cleanly resolved. Just as nonsurgical and surgical dental treatment can exacerbate neuropathic pain, so too may longstanding and untreated dental pain. Crucial to successful management of cases like Jennifer’s and Sandra’s were the informed consent discussions and consultation with medical providers to manage potential extragnathic sources of pain. Ultimately, any patient being evaluated for orofacial pain should be managed similarly. A comprehensive approach to diagnosis, consideration of all sources of pain along with their management, and a thoughtful discussion wherein patients are informed of both risks and benefits of any proposed treatment are essential for positive patient-centered outcomes.

References

Gordon SM, Dionne RA, Brahim J, Jabir F, Dubner R. Blockade of peripheral neuronal barrage reduces postoperative pain. Pain. 1997 Apr;70(2-3):209-15.

Mattscheck DJ, Law AS, Noblett WC. Retreatment versus initial root canal treatment: factors affecting posttreatment pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001 Sep;92(3):321-4.