Treating Patients with Disabilities – An Endodontic Perspective

By Caithlin Williams-Beecher, DMD, MSc

Special Needs and Oral Health

Special needs can be defined as any physical, developmental, mental, sensory, behavioural, cognitive, or emotional impairment or limiting condition that requires medical management, health care intervention and/or use of specialized services programs(1). According to the World Health Organization(2), approximately 1.3 billion people (16% of the world’s population) experience a significant disability.

Fig. 1

Oral health is being free from mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral infections and sores, periodontal disease, tooth decay, tooth loss and other diseases and disorders (3). Of note, patients with special needs exhibit a higher risk for trauma, extensive caries and developing oral diseases. Patients with special needs oftentimes have mental, developmental, or physical disabilities that may render them incapable of understanding, assuming responsibility for or cooperating with preventive oral care procedures (Fig. 2). These conditions allow bacteria to enter the root canal system, resulting in pulpal inflammation or death and periradicular inflammation, which necessitates endodontic therapy to retain the affected tooth or teeth.

Fig. 2

Endodontic Outcomes in Patients with Special Needs

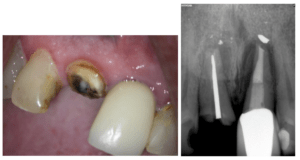

The life expectancy of patients with special needs is increasing and as such they require maintenance of a functional dentition to improve their quality of life(4,5). However, in this population, some dentists prefer to extract teeth needing endodontic therapy rather than performing endodontic treatment due to potential difficulties in patient management (Fig 3).

Fig. 3

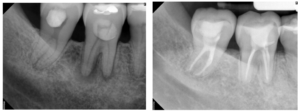

Evaluation of the outcomes of endodontic treatment is a hotly debated topic with over 60 articles being published on the topic. On the contrary, despite there being so many studies and articles, very few address endodontic outcomes in patients with special needs. Within the literature, there are two main thoughts used to classify/categorize endodontic outcomes –success and survival. When considering that endodontic treatment has been successful, the treated tooth must be free from both clinical symptoms and either the absence of or reduction in the size of a pre-existing lesion(6) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Survival, as an outcome is in keeping with providing retention of teeth without any symptoms following endodontic therapy (Fig 5). However, the notion of ‘survival’ does not consider the presence or absence of disease itself(6).

Fig. 5

In a retrospective cohort study by Williams-Beecher et al.(7), 108 teeth that had undergone initial treatment in 61 patients with special needs were evaluated. The majority of these cases (81.5%) were managed without the need for general anaesthesia. The healing rate for initial endodontic treatment was 89.9% and, the primary prognostic factor was no restoration being present at follow-up. In addition, teeth with a definitive restoration placed immediately after the completion of endodontic treatment showed a better healing rate. After a mean follow-up of 79.36 ± 59.6 months, the survival rate was 73% and was correlated with gender (male) and age (>40 years). The most common reason for tooth extraction was unrestorable tooth fracture, an event outside of the control of the clinician.

Extraction vs Retention

There is no “hard and fast” rule when deciding whether to extract or retain a tooth. Decisions should be done on an evidence-based case-by-case basis. Some factors to consider when making your final decision include the:

- The extent of the patient’s disability

- Patient’s oral-health-related quality of life if the teeth are extracted versus retained (especially in cases where there is no intention for prosthetic rehabilitation)

- Feasibility of the patient being able to wear a prosthesis if the tooth is extracted

- Patient’s ability to tolerate treatment

- Patient’s ability to effectively maintain dentition and/or prosthesis

Because many patients with special needs cannot effectively master the use of removable prostheses or do not have the resource to cover fixed or implant-supported prostheses, a shift in the treatment paradigm from extraction to retention is necessary(7).

Managing Endodontic Patients with Special Needs in the Dental Chair

The primary goal of endodontics is to prevent the development of apical periodontitis, or in cases where apical periodontitis has already developed, to create conditions conducive to the healing of periapical tissue. This goal remains the same for patients with or without special needs. Understanding a patient’s cognitive level, oral aversion, sensitivities and triggers to negative behaviours will help to improve the delivery of care and communication (1). If the clinician familiarizes themselves with the special needs of the patient and the concerns of the parent, dental management can be satisfying. The key to treating this group – developing the ability to guide them through their dental experience(8).

Management techniques

- Behaviour management

- Protective stabilization

- Conscious sedation

- General anaesthesia

Conclusion

Endodontic treatment in patients with special needs shows favourable healing and survival rates. If a case can be adequately managed with no need for general anaesthesia, then community-based general dentists, pediatric dentists and endodontists can treat these patients in a private practice setting This would provide these patients with better access to preventive, restorative, and endodontic care rather than being met with the bottlenecks associated with overtaxed and extremely busy hospital dental clinics to treat these patients.

Fig. 6

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Management of dental patients with special health care needs. In: The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Chicago, III(2021), pp. 287-294.

- World Health Organization. Oral health. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/oral-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed: July 2020.

- World Health Organization. Disability. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability#tab=tab_1. Accessed: July 2020.

- Yap, P. Parashos, G.L. Borromeo. Root canal treatment and special needs patients. Int Endod J, 48 (2015), pp. 351-361.

- H. Chung, K.A. Chun, H.Y. Kim, et al. Periapical healing in single-visit endodontics under general anesthesia in special needs patients. J Endod, 45 (2019), pp. 116-122.

- Friedman, C. Mor. The success of endodontic therapy – healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc, 32 (2004), pp. 493-503.

- Williams-Beecher, et al. A retrospective study on Endodontic treatment outcomes in patients with special needs. J Endod, 49 (2023), pp. 808-818.

- A. Dean, D.R. Avery, R.E. McDonald. Dentistry for the child and adolescent. Mosby, Elsevier