When It’s Not Just Endo: Lessons from a Carcinoma Hiding in Plain Sight

By Ji Wook Jeong, DDS, MS

As endodontists, we are trained to diagnose and differentiate complex orofacial pain and periapical disease with precision. But every so often, a case reminds us that not all radiolucencies are endodontic—and not all toothaches are what they seem.

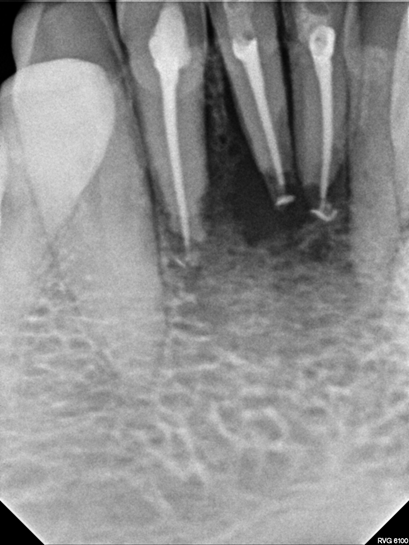

This was the case with a 57-year-old male patient who had previous root canal treatments in the teeth #26, #25, and #24 (Fig.1) because his TMD specialist requested root canal treatments before mouth appliance if any risk of pulpal infection. However, the patient continued to suffer persistent, radiating pain. He had no facial swelling or paresthesia, but he did report difficulty swallowing, ear pain, and limited mouth opening. These signs, while subtle in isolation, became more concerning when considered together.

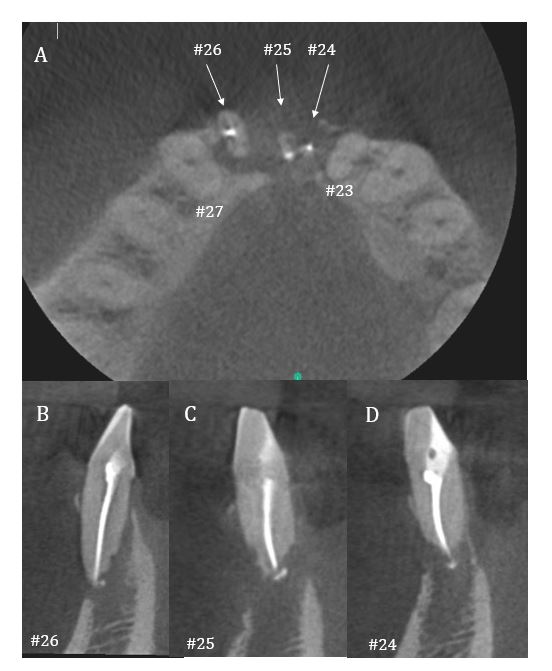

A periapical radiograph revealed a poorly defined radiolucency from tooth #26 to #24 (Fig.1) and CBCT confirmed a through-and-through lesion (Fig.2A) with external root resorption at multiple apices (Fig.2B-D). The case mimicked symptomatic apical periodontitis, but with just enough inconsistency to raise suspicion. For instance, the patient continued to experience cold sensitivity even after root canal treatments on teeth #26, #25, and #24. In hindsight, I believe his extremely low pain threshold may have caused any light contact, including the cotton pellet used in our cold test with Endo Ice—to trigger pain.

Moreover, complicating the diagnosis was the patient’s extensive trauma history: a former boxer, he had suffered repeated dental injuries and head trauma from a previous car accident, followed by Gamma Knife radiosurgery. These factors, combined with his current medication regimen for chronic pain, initially pointed dentists toward a diagnosis involving temporomandibular disorder and persistent odontogenic pain.

I performed root-end surgery on the affected teeth and submitted the tissue for biopsy. The pathology report, which arrived a month later, was sobering: adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare salivary gland malignancy known for its perineural invasion, slow progression, and late distant metastasis (1). The patient was promptly referred to oncology and underwent extensive surgical treatment. However, the adenoid cystic carcinoma had metastasized to the lungs, and he has since been enrolled in clinical trials.

Shift in the Clinical Decision

What made this case so deceptive was its mimicry. The lesion looked endodontic. The symptoms resembled persistent apical periodontitis, albeit with some red flags, such as trismus, dysphagia, and pain radiating to the ears. These were possibly interpreted as signs of temporomandibular disorder, especially given the patient’s complex medical and trauma history. But when the radiographic and clinical signs didn’t match the expected healing trajectory, we chose to biopsy. This decision turned out to be lifesaving.

Clinical and Teaching Lessons

This case reminds us of how we teach endodontic surgery, not just the technical aspects, but also the broader responsibility of differential diagnosis.

In residency programs, we emphasize flap design, root-end resection, ultrasonic device, bioceramic materials and so on. But just as critical is pattern recognition—the ability to identify when something doesn’t fit. In academia, the educators should discuss with residents and dental students the importance of listening closely to the patient’s description of pain, especially when it is constant, severe, and poorly localized. These are often red flags for something beyond the tooth.

Identifying malignancies that imitate endodontic conditions early is key to avoiding treatment delays. Salivary gland cancers represent the second most frequent malignancy mimicking endodontic lesions, with metastatic tumors being the most common (2). More than 80% of malignancies mimicking endodontic pathology cause cortical bone destruction, and adenoid cystic carcinoma often exhibits perineural invasion that contributes to atypical pain patterns (2).

In our case, the patient had no paresthesia or visible swelling, reminding us that the absence of classic signs doesn’t rule out serious disease.

Practical Insights for Clinicians

From this experience, here are five practical clinical tips for clinicians:

- When symptoms don’t follow the script, stop and re-evaluate. Pain that doesn’t respond to properly rendered treatment deserves deeper investigation.

- CBCT is valuable, but doesn’t replace clinical judgment. Radiographic features may suggest non-endodontic origin, but symptoms often provide the first clues.

- Trismus, dysphagia, and bilateral ear pain in an “endo case” should raise concern. These are atypical signs that merit a broader differential diagnosis.

- Always consider biopsy when treating periapical lesions surgically. Even if malignancy is low on your list, histopathology can catch the unexpected.

- We, endodontists, are sentinels of diagnosis, not just technicians. Our role often places us at the first point of contact for serious conditions that mimic dental disease.

Final Reflection

As endodontists, we pride ourselves on resolving pain and saving teeth. But sometimes, our most important contribution is not the procedure we perform, but the decision we make to pause, question, and look deeper into the case.

This case reminded me that the apex is not the end of our diagnostic duty. Sometimes, the real diagnosis lies just beyond it.

A full description of this case is available in my published case report (3).

References

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck–An update. Oral Oncol 2015;51:652-61.

- Schuch LF, Vieira CC, Uchoa Vasconcelos AC. Malignant lesions mimicking endodontic pathoses lesion: a systematic review. J Endod 2021;47:178-88.

- Jeong JW, Varghese IA, Won YK, Vigneswaran N, Kirkpatrick T. Intraosseous adenoid cystic carcinoma mimicking endodontic periapical lesion along with orofacial pain: a case report. Aust Endod J 2025;0:1–5.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Ji Wook Jeong, DDS, MS, is Associate Professor, Department of Endodontics, UTHealth Houston School of Dentistry.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed by authors are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the American Association of Endodontists (AAE). Publication of these views does not imply endorsement by the AAE.