Animals’ Teeth Are Worth Saving, Too!

By Kimberly A.D. Lindquist, D.D.S., M.S.D.

A set of healthy teeth signifies strength in humans as well as in animals. As dentists and dental specialists, we rely on our patients to care for their dentition and report when there are problems or issues. Have you ever wondered what happens when animals have tooth problems? If you are a pet owner, perhaps the veterinarian performed some dental treatment. But what about the wild animals at the zoo? Turns out these exotic animals can also have dental issues.

Animals housed at zoos and animal parks are cared for by zookeepers and caretakers. Not only do these caregivers feed the animals, clean their living spaces and work to keep them healthy, but they also closely observe the animal’s appearance and activity for changes that may indicate pain, illness, or disease. At the Lake Superior Zoo in Duluth, MN, the zookeepers for a recently acquired Allen’s swamp monkey, Noqui, noticed an oozing sore under his eye and asked the zoo veterinarian to have a look. An Allen’s swamp monkey (Figure 1) is native to the Congo Basin in Africa. They live in social groups of up to 40 animals, communicating with different calls, gestures, and touches. Noqui was rescued from living alone in a small cage as someone’s “pet.” The zoo was hoping to integrate him back into a more natural habitat and social setting.

Unlike most of our patients, animals (especially wild animals) don’t willingly come to the “dentist” for an intraoral examination. In this case, Noqui was tranquilized so the zoo veterinarian could have a closer look. Noqui had broken or worn his maxillary right canine exposing the pulp canal, resulting in pulpal necrosis and subsequent extraoral sinus tract formation (photo 2). Typically, abscessed teeth in wild animals are removed; however, monkeys are primates (like humans) and are bullied and ostracized by their peers if missing a prominent tooth like the canine. Noqui needed root canal treatment. This is where I come into the story.

My dental assistant met the zoo veterinarian one weekend at the Emergency Veterinarian clinic. Dr. Beyea was the emergency vet that day. Her main practice was attending to the animals at the Lake Superior Zoo. While making small talk, my dental assistant explained that she worked for an endodontist and went on to explain what an endodontist did. Curiously, Dr. Beyea asked my assistant if I had ever treated a wild animal and if I would be willing to treat one. She described Noqui’s issue and thought perhaps I could help him. Since the zoo was hoping to integrate Noqui into the existing exhibit and have him mate with at least one of the females, he was going to need a root canal treatment on his diseased tooth. My dental assistant wasted no time explaining this encounter and immediately offered to assist me if I would treat the monkey. I was humbled and excited to try my skills on an exotic animal.

Although I tried to prepare for my time with Noqui, there is not a lot of information specific to monkey teeth/anatomy/etc. I looked for any information regarding monkey dental anatomy or diagrams showing the dental anatomy of swamp monkey dentition, but there was really nothing helpful. After talking with a local veterinarian who had completed dental treatment on some of his “patients,” I borrowed some longer hand files and other instruments from the University of MN School of Veterinary Medicine. Even though swamp monkeys can reach a full body length from 45-60 cm (not including a 50cm long tail) the canine tooth would likely be longer than 31mm instruments I possessed. I packed up my equipment including my microscope and my dental assistant and traveled to the zoo surgical suite to meet and treat the monkey.

Noqui was brought into the operating suite in a “homemade” crate, where he was tranquilized. Once sedated, he was placed onto the operating table (photo 3), intubated, and given general sedation. His vitals were continually monitored by Dr. Beyea very much like a human is monitored under general anesthesia. A striking difference to a human operating room experience were the ropes restraints on his limbs as well as the multiple handlers nearby with tranquilizers at the ready.

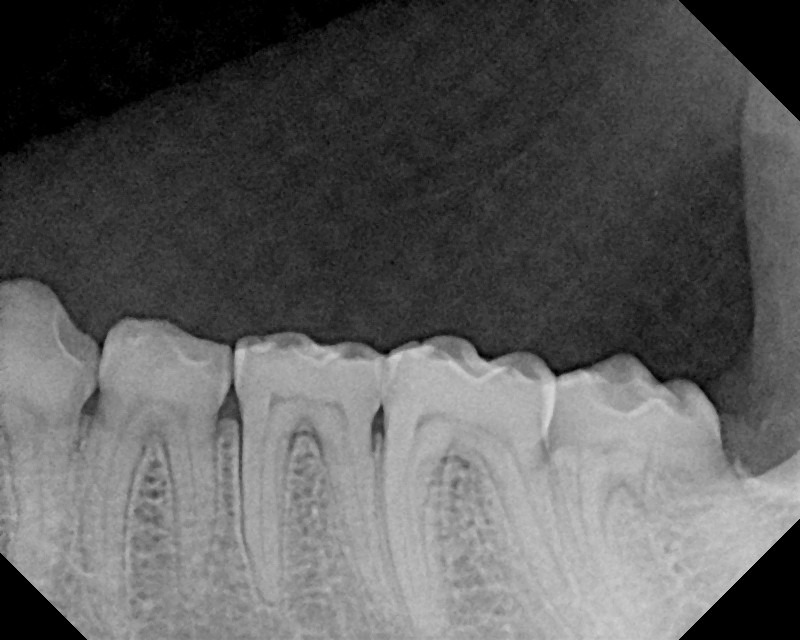

I attempted to expose a pre-operative periapical radiograph of the affected canine, but due to the shallow palate and long roots- diagnostic radiographs with my sensor were quite difficult to get. Dr. Beyea requested a full mouth set of radiographic images for evaluation to rule out other dental issues. Besides the long, curved canine teeth, Noqui had a very similar dentition to us humans. Instead of premolars, this animal had “mini” molar teeth resembling deciduous molars (photo 4). Swamp monkeys are omnivores and eat a variety of fruits, seeds, insects, fish, shrimp, snails, other small invertebrates, and leaves.

Prior to placing the rubber dam (yes — rubber dam isolation even on the monkey) I evaluated the opposite maxillary canine to get an idea of how much was missing from the broken canine tooth (photos 5-6).

Under microscopic magnification, debridement and instrumentation were completed (photos 7-8). Even with the longer hand instruments, I had issues getting to length or knowing the true length of this tooth. Time is of the essence when treating an animal under general sedation (just like a human) and so ultimately, I did my best. I finally got a “good” final radiograph (photo 9). I was disappointed to see my obturation was sort of the radiographic apex, but I knew was thorough in my instrumentation and irrigation, so I hoped Noqui’s body would heal, nonetheless.

Although full coronal restoration is ideal after endodontic treatment on a broken-down tooth, Noqui received a composite resin to seal the orifice and seal the cavity prep. After I completed the root canal treatment, a separate veterinarian (who had been observing) took over and completed full dental evaluation and prophylaxis.

As Noqui went into “recovery” the next patient was being prepped, a silver fox with suspected urinary tract issues. My patient was completed, but Dr. Beyea had others to see. I came away with a new appreciation for the handlers and keepers of these wild animals. The care and attention these animals receive is more than I ever imagined.

I didn’t see Noqui for an annual recall, but I did find out that he was fully integrated into the zoo’s exhibit and had become a proud papa. I consider this a successful outcome.

Allen’s swap monkey, Figure 1

Extraoral lesion

Noqui sedated

Left posterior

Intraop image

Tied down and RDI

Dr. Lindquist

Dr. Lindquist works in Duluth, Minn., and specializes in Endodontics.