Periapical Microsurgery: Embracing the Renaissance

By Peter Z. Tawil, D.M.D., M.S., FRCD(C)

By Peter Z. Tawil, D.M.D., M.S., FRCD(C)

Periradicular surgery is an important treatment option in modern endodontic practices and has been a crucial asset for those practitioners that embraced it (1). In the early 2000s as the implant era was thriving, prosthodontists and periodontists favored dental implants over retreatment to replace non-healed endodontically treated teeth. Esteemed educators like Dr. Gordon Christensen were advocating for dental implants to replace non-healed endodontic teeth as the published literature on the outcome of retreatments did not appear to be as favorable (2). Since then there has been a steady shift in philosophy.

The “Renaissance Era of Endodontics” is taking place and it’s up to us as endodontists to seize this opportunity to make our specialty shine.

Long term data on dental implants has shown its limitations and the literature is now flooded with publications in regards to the management of failing dental implant prostheses (3). Implant component loss is the most common source of failure (be it biological or mechanical in nature) and tends to increase over time. Many implant complications are due to the lack of a periodontal ligament around an implant body, which results in abutment screw loosening, abutment fractures, prosthesis fracture, etc with occlusal challenges (3). Although dental implants remain a great option for replacement of the “missing” dentition, they should not always be the first option to replace the “existing” dentition. Current surgical endodontic protocols (4) used in conjunction with contemporary root-end filling materials have shown excellent success rates (5-7). The increased predictability and success associated with apical microsurgeries are thanks to multiple factors, which we will review.

Enhanced Visualization

Enhanced vision is a concept we all understand as endodontists as we appreciate the improved treatment quality we obtain by using a microscope for our traditional endodontic treatments. It goes without saying that we can only treat what we can see (8). Seeing what we do is crucial to what we aim to achieve surgically. Direct vision through proper microscope positioning is a crucial concept. We can get better practitioner dexterity and treatment predicability by working in direct vision. This is achieved by having a microscope with multiple articulations settings or by using a magnification unit, such as the MoraVisionTM, so the apex of the tooth is always facing the practitioner’s core. Operator positioning is critical to achieving ideal vision and is a vital aspect of the training I focus on when I mentor colleagues in their offices. We have to be open-minded in moving our operating location to accommodate enhanced vision. Furthermore, when working on posterior teeth, a slight bevel is oftentimes needed to achieve ideal vision of the apical complex. The bevel is done as much as practical during the inspection and management of the apical complex and can be flattened after the root-end filling is placed to make sure 3mm of the lingual part of the root is removed. Yet another factor in this visualization element is the quality of the operating light. New LED light sources have provided us an affordable long-lasting light source with 100,000 to 200,000 Lux. Additionally, we have several filters that can enhance the visualization as well as small microscopic LED transilluminators that can assist us in analyzing the root end system (8). The final factor in enhancing our visualization is removing the distractors. Thanks to more biological hemostatic agents, we can now achieve ideal hemostasis with minimal side effects to tissue healing. Various aluminum chloride pastes/gels are now available to replace the biologically toxic oil-based ferric sulfate. Aluminum chloride products can be used to replace or in addition to the classic epinephrine-based Racellet® Pellets. The main advantage of aluminum chloride is that there is no risk of leaving cotton fiber remnants in the surgical site and its water solubility makes it easy to rinse out at the conclusion of the surgery (9).

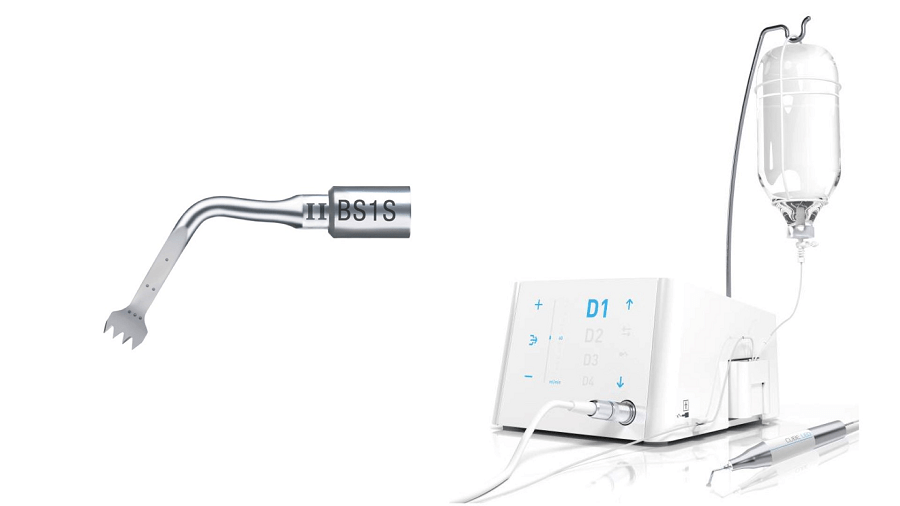

Minimizing Risk Through the Use of the Piezotome

One of the drawbacks of surgeries used to be the risks associated with the use of a high-speed handpiece in proximity to vital structures such as the mental foramen, the sinus, the inferior alveolar nerve, the lingual artery, etc. Newer Piezotome units are now available on the market that are a lot more affordable than in the past [Fig 1]. Using a Piezotome minimizes the surgical risks as these units do not cause damage to soft tissues and can be used to preserve the buccal plate through an enhanced bony-lid access (10). Thanks to this new technology, periapical microsurgery can now be done in a safe fashion minimizing the risk of major complications and paresthesia (11).

Dentinal Defect Management

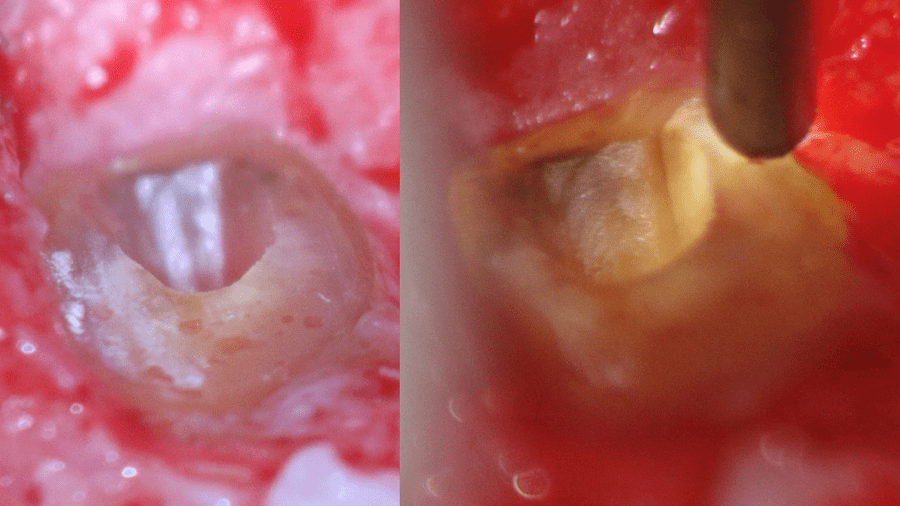

Recent endodontic literature has suggested that dentinal defects (also referred to as micro-cracks or craze lines) on the root canal walls can appear after root canal treatments and especially after endodontic retreatment procedures (2). Dentinal defects are incomplete fracture lines that interrupt the integrity of the dentin on the root-end surface (12). Dentinal defects are best identified with LED transillumination of the root-end resected surface [Fig.2] and have to be removed to avoid compromising the long term treatment outcome (8,13). It is speculated that radicular dentinal defects may propagate during normal function and result in potential pathways for leakage or in root fractures (14). Dentinal defects are more prone to occur in older teeth due to their microstructure change, corresponding chemical composition, and increase in collagen cross-linking (15). When present, they tend to be most severe near the root apex (15), which is thankfully the apical segment that is typically resected during apical microsurgery.

Apical Seal

The success of endodontic microsurgery is mostly due to the enhanced apical seal that we can obtain through a retrograde treatment approach (16). Cutting off the amino-acid source that comes through the apical fluid from the root canal system is key to induce starvation and eradication of any remaining anaerobe bacteria in the root system (16). This is achieved by resecting the apical 3mm where most canal lateral anatomy is located (17), by creating a 3mm root-end preparation along the long axis of the root using surgical endodontic tips (18) and by sealing the system with a modern biocompatible material (7).

Grafting

Although grafting is not always needed in apical surgery (19), it becomes crucial when a periodontal defect is found upon flap reflection (20). A true apico-marginal defect needs to be addressed to maintain the long term success of this procedure (20). There are different techniques and materials that can be utilized depending on the extent and depth of the defect (20). The goal of grafting is to slow down the epithelial growth and give time for the bony matrix to re-establish the bony housing support around the tooth.

Conclusion

It’s up to endodontists as specialists in “saving the natural dentition” to step up and embrace microsurgical endodontics and what this treatment can offer to our patients and our dental communities. Periapical microsurgery is a great asset to have in endodontic practices. This renaissance opportunity in endodontics hinges on the basis of endodontists embracing latest and improved microsurgical techniques as well as properly educating referral sources so that treatment planning can change accordingly. The speciality of endodontics has a mission of saving the natural dentition, and through looking for opportunities to perform more periapical microsurgery in leu of implant placement, we can do just that.

Figures

Figure 1

Piezotome CUBE with the BS1S bone cutting piezotome tip (Acteon)

Figure 2

LED transillumination showing a dentinal defect on the P wall of the resected root tip

References

- Boykin MJ, Gilbert GH, Tilashalski KR, Shelton BJ. Incidence of endodontic treatment: a 48-month prospective study. J Endod 2003 Dec;29:806-809.

- Tawil PZ, Arnarsdottir EK, Phillips C., Saemundsson S.R. Periapical Microsurgery: Do Root Canal Retreated Teeth Have More Dentinal Defects? J Endod, 2018, 44:1487-91.

- De Kok IJ, Duqum IS, Katz LH, Copper LF. Management of Implant/Prosthodontic Complications. Dent Clin North Am 2019 Apr;63:217-231.

- Kim S, Kratchman S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod 2006 Jul;32:601-623.

- Rubinstein RA, Kim S. Long-term follow-up of cases considered healed one year after apical microsurgery. J Endod 2002 May;28:378-383.

- Chong BS, Pitt Ford TR, Hudson MB. A prospective clinical study of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate and IRM when used as root-end filling materials in endodontic surgery. Int Endod J 2003 Aug;36:520-526.

- Kohli MR, Berenji H, Setzer FC, Lee SM, Karabucak B. Outcome of Endodontic Surgery: A Meta-analysis of the Literature-Part 3: Comparison of Endodontic Microsurgical Techniques with 2 Different Root-end Filling Materials. J Endod 2018;44:923-931.

- Arnarsdottir EK, Karunanayake GA, Phillips C, Saemundsson SR, Tawil PZ. Periapical Microsurgery: Assessment of different types of Light Emitting Diode transilluminators in detection of dentinal defects. J Endod, 2020, 46:252-7.

- Menéndez-Nieto I, Cervera-Ballester J, Maestre-Ferrín L, Blaya-Tárraga JA, Peñarrocha-Oltra D, Peñarrocha-Diago M. Hemostatic Agents in Periapical Surgery: A Randomized Study of Gauze Impregnated in Epinephrine versus Aluminum Chloride. J Endod, 2016, 42:15831587.

- Khoury F, Hensher R. The bony lid approach for the apical resection of the lower molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987;16(2):166-170

- Lee SM, Yu YH, Wang Y, Kim E, Kim S. The Application of “Bone Window” Technique in Endodontic Microsurgery. J Endod 2020;46:972-880.

- Shemesh H, Bier CA, Wu MK, et al. The effects of canal preparation and filling on the incidence of dentinal defects. Int Endod J 2009;42:208-13.

- Tawil PZ, Saraiya VM, Galicia JC, Duggan DJ. Periapical microsurgery: the effect of root dentinal defects on short- and long-term outcome. J Endod 2015;41:22-27.

- Tawil PZ, Arnarsdottir EK, Coelho MS. Root Originating Dentinal Defects: Methodological aspects and clinical relevance. Evid Based Endod, 2017,2:1-8.

- Yan W, Montoya C, Øilo M, Ossa A, Paranjipe A, Zhang H, Arola D. Reduction in Fracture Resistance of the Root with Aging. J Endo 2017;43:1494-1498.

- Tawil PZ, Trope M, Curran AE, Caplan D, Kirakozova A, Duggan D, Teixeira FB. Periapical Microsurgery: An In Vivo Evaluation of Root-End Filling Materials. J Endod, 2009; 35:357-62.

- De Deus QD. Frequency, location, and direction of the lateral, secondary, and accessory canals. J Endo, 1975;361-366.

- Tawil PZ. Periapical Microsurgery: Can Ultrasonic Root-End Preparations Clinically Create or Propagate Dentinal Defects? J Endod, 2016, 42:1472-5.

- Crossen D, Tawil P, Morelli T, Tyndall D. Periapical Microsurgery: A 4-D Analysis of Healing Patterns. J Endod, 2019, 45:402-5.

- Von Arx T, AlSaeed M. The use of regenerative techniques in apical surgery: A literature review. Saudi Dent J, 2011, 23:113-127.