Endodontic and Periodontic Dilemmas: Bridging the Diagnostic Divide

By Drs. Sami Chogle and Pinelopi Pani

Endodontic-periodontal lesions have complicated etiologies and pathogenic mechanisms, including unique anatomical and microbiological characteristics and contributing factors. In dental practice, few clinical presentations challenge practitioners more than these lesions and the etiological complexity often leads to difficulties in determining tooth prognosis and appropriate treatment. The proximity and interconnection create a bidirectional relationship that allows disease in one tissue to affect the other, resulting in diagnostic gray zones. As specialists we frequently encounter cases that underscore this complexity and demand not only our technical capabilities but also our diagnostic accuracy and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Anatomical Convergence, Clinical Divergence

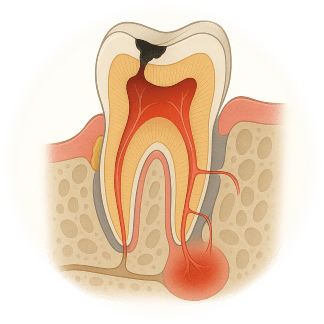

Dental pulp and periodontium have embryonic, anatomic and functional inter-relationships1. From a biological perspective, the pulp and periodontium function independently, but pathologically, their communication channels (apical foramen, lateral and accessory canals, dentinal tubules) facilitate the spread of bacteria, toxins, and inflammatory mediators. Whether disease initiates in the pulp or the periodontium (figure 1), the resulting lesion can mimic either condition.2 A necrotic pulp can manifest with draining sinus tracts and deep periodontal pockets, imitating periodontal breakdown.3,4,5 Conversely, chronic periodontitis that progresses apically may lead to a cumulative damaging effect to the pulp of more rarely to pulp necrosis.5,6,7,8 Clinical studies have shown that periodontal disease and its treatment rarely results in teeth needing endodontic treatment when the cementum remains intact.9,10 The only exception to this is when the periodontal condition is of such an extent that a pocket reaches the apical foramen. In such advanced periodontal disease, the pulp’s defenses can in some cases be overwhelmed, thus succumbing to infection and ultimately pulp necrosis occurs. The difficulty lies in distinguishing primary disease origin when clinical signs overlap.

Diagnostic Challenges

Misdiagnosis often arises from an overreliance on isolated findings—probing depth, radiographs, or symptoms—without integrating a full diagnostic picture. This may not account for additional findings such as cracks, fractures, resorptive defects or cemental tears. A comprehensive approach including Vitality testing (thermal, electric), Radiographic evaluation with CBCT, tracing of sinus tracts, if present, and comprehensive probing for attachment loss along with mobility assessment could help reduce diagnostic error. A new classification, proposed by the World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions in 201811, focused on the prognosis of involved tooth. The classification is based primarily on the following signs and symptoms of the involved tooth: presence/absence of root damage and anatomic problems; presence/absence of full-mouth periodontitis; and severity and extent of the periodontal defect of the affected tooth, including furcation involvement.

Strategic Sequencing in Therapy

A significant dilemma is not just diagnosis, but treatment sequencing as well. Based on evidence (REF) and clinical observation, we advocate addressing the endodontic component first when the pulp is non-vital. This helps eliminate intraradicular infection, allowing time to observe healing and reevaluate the periodontal status. Periodontal therapy should follow only, if necessary, guided by the healing response after root canal therapy. On the other hand, pulp necrosis from periodontitis is rare; massive bone loss must reach the apex before bacteria threaten the canal.7 Vital pulps tolerate periodontal surgery well with only mild pulpal inflammatory reactions. But more importantly, re-attachment in periodontal therapy outperforms expectations when the pulp remains intact.12 Thus, intervention should be biologically justified—never reflexive.

When Root Damage Changes the Game

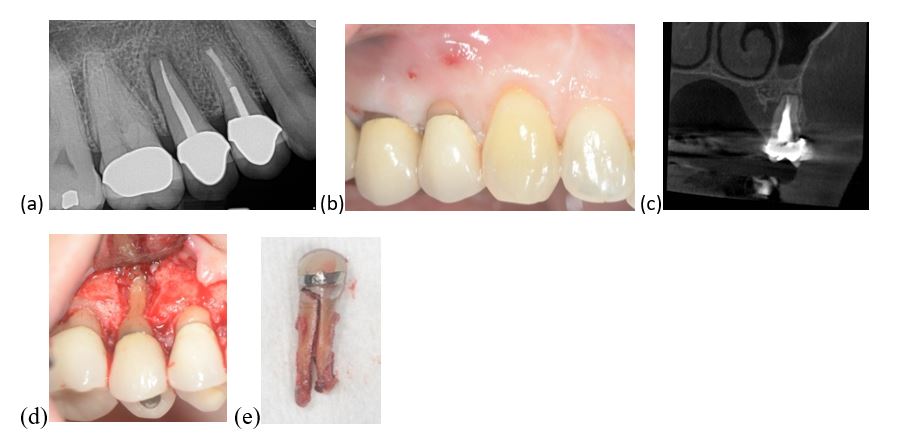

Treatment attempts for vertical root fractures remain hopeless, prompting extractions to prevent futile costs. Other failures may result as a consequence of delayed detection and referral, incomplete canal disinfection, ignored mobility, existing root damage (e.g. microfractures, cemental tears) and patient non-compliance. (Fig 1.) By contrast, external cervical resorption (ECR) deserves nuance. Since endodontic obturation alone seldom halts ECR, a combined may be mandatory. And classifying the stage of ECR utilizing a limited-FOV CBCT would influence the endodontic-periodontal surgical intervention prognosis.13

Conclusion

Endodontic and periodontal dilemmas reflect the interconnected nature of dental tissues—and the importance of integrated clinical thinking. As tools evolve and diagnostic precision improves, these challenges will remain part of daily practice. But with thorough evaluation, coordinated care, and respect for biological principles, we can resolve even the most complex cases with confidence.

References

- Mandel E, Machtou P, Torabinejad M. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of endodontic and periodontal lesions. Quintessence Int. 1993;24(2):135–9

- Simon JH, Glick DH, Frank AL. The relationship of endodontic-periodontic lesions. J Periodontol. 1972; 43: 202–208.

- Seltzer S, Bender IB, Ziontz M. The interrelationship of pulp and periodontal disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963; 16: 1474–1490

- Rubach WC, Mitchell DF. Periodontal disease, accessory canals and pulp pathosis. J Periodontol. 1965; 36: 34–38.

- Langeland K, Rodrigues H, Dowden W. Periodontal disease, bacteria, and pulpal histopathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974; 37: 257–270.

- Czarnecki RT, Schilder H. A histological evaluation of the human pulp in teeth with varying degrees of periodontal disease. J Endod. 1979;5(8):242–53.

- Zehnder, M. Endodontic infection caused by localized aggressive periodontitis: A case report and bacteriologic evaluation. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontics 2001; 92, 440–445.

- Zehnder M, Gold SI, Hasselgren G. Pathologic interactions in pulpal andperiodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29: 663–671.

- Bergenholtz G, Nyman S. Endodontic complications following periodontal and prosthodontic treatment of patients with advanced periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1984; 55: 63–68.

- Jaoui L, Machtou P, Ouhayoun JP. Long-term evaluation of endodontic and periodontal treatment. Int Endod J 1995; 28: 249–254.

- Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, Fine DH, Flemmig TF, Garcia R, Giannobile WV, Graziani F, Greenwell H, Herrera D, Kao RT, Kebschull M, Kinane DF, Kirkwood KL, Kocher T, Kornman KS, Kumar PS, Loos BG, Machtei E, Meng H, Mombelli A, Needleman I, Offenbacher S, Seymour GJ, Teles R, Tonetti MS. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018 Jun;89 Suppl 1:S173-S182.

- Cortellini P, Tonetti MS. Evaluation of the effect of tooth vitality on regenerative outcomes in infrabony defects. J Clin Periodontol. 2001 Jul;28(7):672-9.

- Patel S, Foschi F, Mannocci F, Patel K. External cervical resorption: a three-dimensional classification. Int Endod J. 2018 Feb;51(2):206-214.

Fig. 1: A challenging clinical presentation: Teeth #20 and #21 presented with diffuse swelling but minimal pain on percussion and bite. Both teeth did not respond to sensibility testing.

Fig. 2: Tooth #4 presented with (a) PDL widening, peri-apical radiolucency, (b) deep isolated pocket mid-buccally and a draining fistula. (c) A CBCT scan showed a J-shaped lesion. The suspicion of a vertical root fracture (VRF) is high, which was also confirmed via a diagnostic flap (d). (e)Teeth with VRF have a hopeless prognosis and need to be extracted.

Dr. Sami Chogle is Chair and Program Director, Department of Endodontics, Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine. Dr. Pinelopi Pani is Clinical Associate Professor, Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed by authors are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the American Association of Endodontists (AAE). Publication of these views does not imply endorsement by the AAE.