External Invasive Resorption: Conceptions and Misconceptions

By Matthew Malek, D.D.S.

External Invasive Resorption (EIR) has been an enigma for endodontists for generations. Recent advancements in histological and Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic (CBCT) imaging have increased our knowledge of EIR, though compared to other types of resorption, it remains limited.

In addition to our limited understanding, historically, certain misinformation concerning the nature and causes of EIR has developed over time into various misconceptions or hypotheses that largely remain unfounded or unproven. In this article, rather than offering new information on EIR, we review and assess the veracity of some of these concepts and theories in order to provide a clearer picture of the current state of our understanding of EIR.

1: Terminology

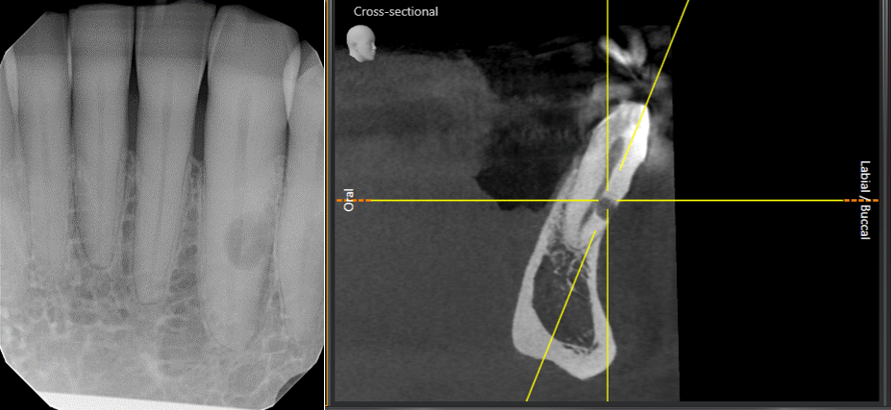

This lesion is known by many different names, with sources citing more than 10 different terms used in the literature to refer to it. Variation in terminology not only causes confusion among researchers and practitioners, but it also can be misleading for novice leaners. For example, the use of the word “cervical” in many of the terms referring to this lesion implies that this resorption is the disease of the cervical part of the tooth, which a misconception. This lesion is in fact a disease of a specific location on the external wall of the tooth, a location that is below the gingival epithelium and above the crestal bone. Although this location often is at the level of the cervical part of the tooth, but in many cases it varies depending on the epithelium and bone level. An example would be figure 1 in which the lesion is obviously not at the cervical area of the tooth.

Figure 1: Left Image: Tooth #22 with a resorption at mid-root level. Right image: A sagittal view of tooth #22 showing the resorptive defect and its relationship to the buccal crestal bone level.

2: Affected Teeth

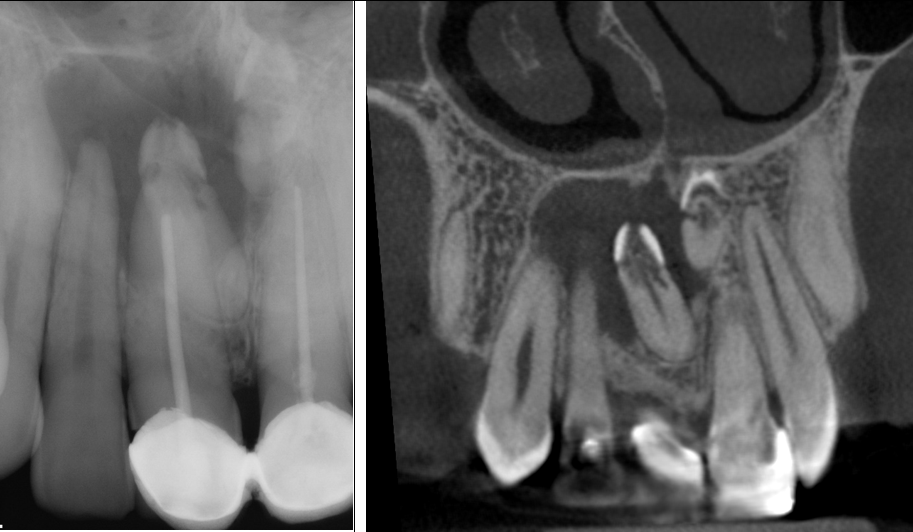

Due to its pathophysiological nature, EIR’s development and progression requires damaged cementum, some level of inflammation, presence of connective tissue, and a stimulating factor, all of which can exist on any tooth, whether permanent or primary, erupted or unerupted. When it affects an unerupted tooth, there is a chance of ankylosis, which in turn may prevent eruption of the tooth and require surgical intervention. Figure 2 is an example of a rare case in which the two impacted supernumerary teeth have been affected by EIR.

Figure 2: Left image: Periapical radiograph of two impacted supernumerory teeth involved with EIR. Right image: A coronal view of the same area showing the two teeth involved with EIR.

3: Types

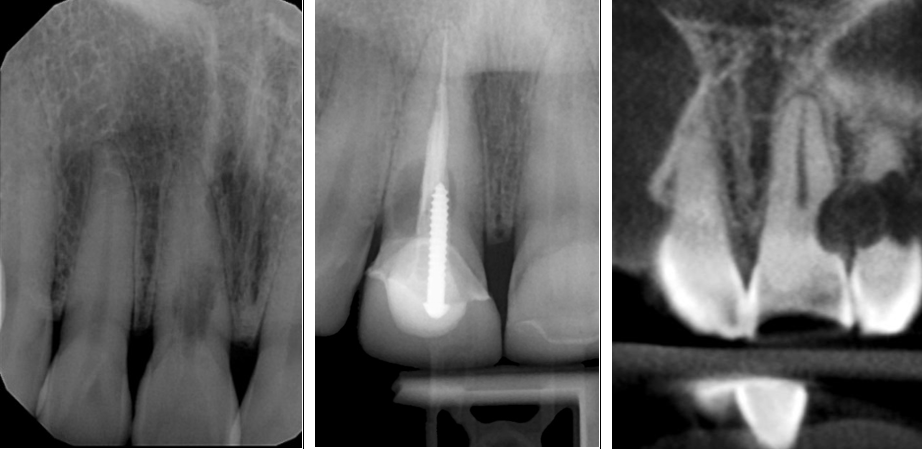

Discussion of EIR often brings to mind its most common type, while the literature defines and describes at least three distinct types of EIR. The first type is the typical and common individual EIR that affects one or more vital teeth. The second type is the individual EIR that affects one or more non-vital or previously treated teeth. Compared to the first, this type is usually: a) more aggressive, b) radiographically more lucent, and, c) lacks bone-like material deposition. The third type is the Multiple Idiopathic type which always involves multiple teeth, sometimes even the whole dentition. It is extremely aggressive and usually initiates at the mesial or distal cemento-enamel junction, as opposed to buccal or lingual side of the tooth. This last type can be associated with genetic factors.

Figure 3: Left image: EIR on a vital tooth (#8). Middle image: EIR on a previously treated tooth (#8). Right image: Multiple Idiopathic EIR (all dentition of this patient was involved).

4: Causes

No definite causes have been identified for this lesion. Strong association has been found between EIR and some factors, such as orthodontic treatment and trauma (acute or chronic (like grinding)); however, none of them are a cause, but rather contributing factors. Moreover, the hypothesis that treating parafunctional habits or halting orthodontic treatment will arrest the resorption process warrants further research. In order to fully understand the etiology of EIR, perhaps the focus should be on the pathobiological pathways leading to resorption which require further research in the future.

The other unproven hypothesis regarding the contributing factors is the association between EIR and Feline External Resorption. The concept of viral transmission between cats and humans is relatively popular, most likely due to its interesting nature and historic background. It is important to know that there has not been any true evidence of such transmission. Moreover, many of the patients with EIR deny close contact with a cat and there has not been any evidence from the owners of diseased cats exhibiting EIR. One of the hypotheses on the pathogenicity of viral infection leading to EIR is the spread of the virus along nerve paths. Multiple EIR on different quadrants, do not support the neural pattern of the disease. Moreover, Feline Odontoclastic Resorption Lesion in cats is a syndrome that includes subgingival lesions, granulomatous or hyperplastic gingiva, none of which has been proven to be linked to EIR in humans. Finally, successful replication of a viral pathogen in a host is a complex process involving many interactions and thus extremely difficult. It is a rather large leap to link root resorption in humans to a virus which not only does not normally transmit but its causal association with resorption in animals is also under question.

5: CBCT

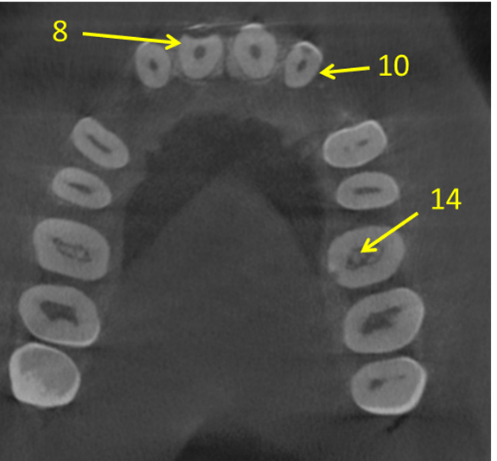

Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) is the imaging modality of choice in diagnosis of EIR and treatment planning. Obtaining a CBCT of a tooth that requires treatment is mostly agreed upon, but there is a hesitation in taking a larger field of view CBCT of these cases or of a tooth that is being monitored due to its extent. Obtaining a CBCT of a tooth that is not planned for treatment is of course not always necessary, but sometimes it may be worth considering. Cases with multiple EIR are not scarce. These cases are usually identified radiographically by exhibiting multiple teeth without any local factors (such as trauma). In these cases, not all affected teeth are at the same stage. Some may have already been developed and are in their late (Heithersay class 3 or 4) stages (and thus visible on radiographs) and others may be in their incipience stage (and thus not necessarily visible on radiographs). As treating EIR in its initial stages is more favorable that in later stages, taking a larger field CBCT in individuals who present with more than one EIR on radiographs, especially if the lesion is not associated with any local contributing factor, could be highly beneficial in detecting other incipient lesions in other parts of the dentition not yet visible in radiographs (Figure 4). This approach can potentially lead to diagnosis and treatment of many lesions at their initial stages with high prognosis rate in patients with multiple EIR and thus it is believed to still be in adherence to the principle of “As Low As Reasonably Achievable” (ALARA).

Figure 4: A scan was taken to evaluate EIR on #8 and #10 both visible on radiographs. The scan also shows an EIR lesion on #14 which was not originally visible on the radiograph.

The goal of this article was to review and discuss certain concepts in relation to EIR that may have been subject to controversies in order to provoke thought and perhaps add some clarity on our current understanding of EIR. There are many other areas related to EIR that warrant discussion but beyond the scope of this piece. The arguments provided in this paper are based on the current evidence, as well as personal experience and observation. As more research is conducted in the future, more evidence and reliable explanations will serve to better shape and guide our discussion in this area and increase our scientific understanding on more aspects of EIR.

References

AAE and AAOMR Joint Position Statement. Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics – 2015/2016 update.

Becker, A., I. Abramovitz, and S. Chaushu, Failure of treatment of impacted canines associated with invasive cervical root resorption. Angle Orthod, 2013. 83(5): p. 870-6.

Heithersay, G.S., Invasive cervical resorption: an analysis of potential predisposing factors. Quintessence Int, 1999. 30(2): p. 83-95.

Heithersay, G.S., Clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic Features of Invasive Cervical Resorption. Quintessence Int, 1999. 30(2): p. 27-37.

Hofmann-Lehmann, M., et al., Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection leads to increased incidence of feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions (FORL). Vet Immunol Immunopathol, 65 (1998), pp. 299-308.

Liang, H., et al., Multiple Idiopathic Cervical Root Resorption: Systematic Review and Report of Four Cases. Dentomaxillofacial Raiology. 2003. 32:150-155.

Mavridou, A.M., et al., Descriptive Analysis of Factors Associated with External Cervical Resorption. J Endod, 2017. 43(10): p. 1602-1610.

Mavridou, A.M., et al., Understanding External Cervical Resorption in Vital Teeth. J Endod, 2016. 42(12): p. 1737-1751.

Mavridou, A.M., et al., Understanding External Cervical Resorption Patterns in Endodontically Treated Teeth. Int Endod J, 2017. 50: p. 1116-1133.

Mavridou, A.M., et al., A novel multimodular methodology to investigate external cervical tooth resorption. Int Endod J, 2016. 49(3): p. 287-300.

Mavridou, A.M., et al., A clinical approach strategy for the diagnosis, treatment and evaluation of external cervical resorption. Int Endod J, 2022. 55(4): p. 347-373.

Pindborg, J.J.r., Pathology of the dental hard tissues. 1970, Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

Rodd, H.D, et al., External Cervical Resorption of a Primary Canine. Int J P Dent, 2005. 15:375-379.

Qin, W., et al., Multiple Cervical Root Resorption Involving 22 Teeth—A Case with Potential Genetic Predisposition.

Shemesh, A., et al., External invasive resorption: Possible coexisting factors and demographic and clinical characteristics. Aust Endod J, 2019. 45(2): p. 141-145.

Von Arx, T. et al., Himan and Feline Invasive Cervical Resorptions: The Missing Link?—Presentaiton of Four Cases. J Endod 2009. 35:904-913.

Yerex, Katherine, Human-Feline Oral Microbiome Cross-Species Transmission, and Its Association with Idiopathic Tooth Resorption. A Thesis. Department of Oral Biology University of Manitoba.