What Happens When Everything Goes Wrong? Errors and Complications in Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment—and How to Make It Right?

By Christine I. Peters, DMD; Bettina Basrani, DMD, MS, PhD; and Ove A. Peters, DMD, MS, PhD

Almost every clinician who performs root canal therapy has lived some dreadful moment leading to a halt of treatment: something does not look and feel right or behaves incorrectly. Anatomy surprises us, the root canal is not to be found or is tight and the instrument suddenly looks shorter. Perhaps there is unexpected bleeding. Abrupt pain could be experienced during treatment. The patient returns the next day with a swelling, or worse, with a story that begins, “Ever since you treated me yesterday, my face feels different.”

Endodontic treatment follows a structured sequence: diagnosis, access, cleaning, shaping, and obturation—but biology rarely adheres strictly to protocol. Patients bring complex medical, dental, and emotional histories that influence outcomes in ways we cannot always foresee.

We hope mishaps never occur, but the reality is that procedural errors and complications are an inherent part of endodontic practice. Entire textbooks1 have been devoted to endodontic mishaps because, statistically, they can happen to every clinician over a long enough timeline. What matters most is not whether errors occur, but how we recognize them, respond to them, and prevent them from happening again.

At the 2025 AAE Annual Meeting in Boston, our session “What Happens When Everything Goes Wrong?? Errors and Complications in Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatments—And How to Make It Right” gave us an opportunity to explore serious, sometimes surprising events that can occur during routine procedures. We explored a broad spectrum of complications ranging from misdiagnosis and non-healing lesions to access errors, irrigation accidents, subcutaneous emphysema, file separation, and unusual anatomical variations. Some of these events are rare; others are preventable missteps that can occur particularly when we are rushed, fatigued, or working in anatomically challenging situations.

In this Communiqué contribution, we expand on two consequential classes of complications: irrigation-related accidents and shaping-related mishaps. Clinicians consistently identify root canal treatments as stressful2: They share common themes: anatomical complexity, loss of control at a critical moment, and the importance of deliberate decision-making once a problem arises.

Our goal is to provide practical guidance and pragmatic prevention advice, so that when complications occur, clinicians have both a systematic approach for managing them and the confidence to make the right decisions for their patients: clinically, ethically, and emotionally.

As we emphasized at the AAE Meeting in Boston, mistakes happen and are not the end of the road. They are opportunities for reflection and refinement. When clinicians understand not only what went wrong, but why, our profession as a whole becomes safer and stronger.

Irrigation Mishaps: When Chemistry Meets Anatomy

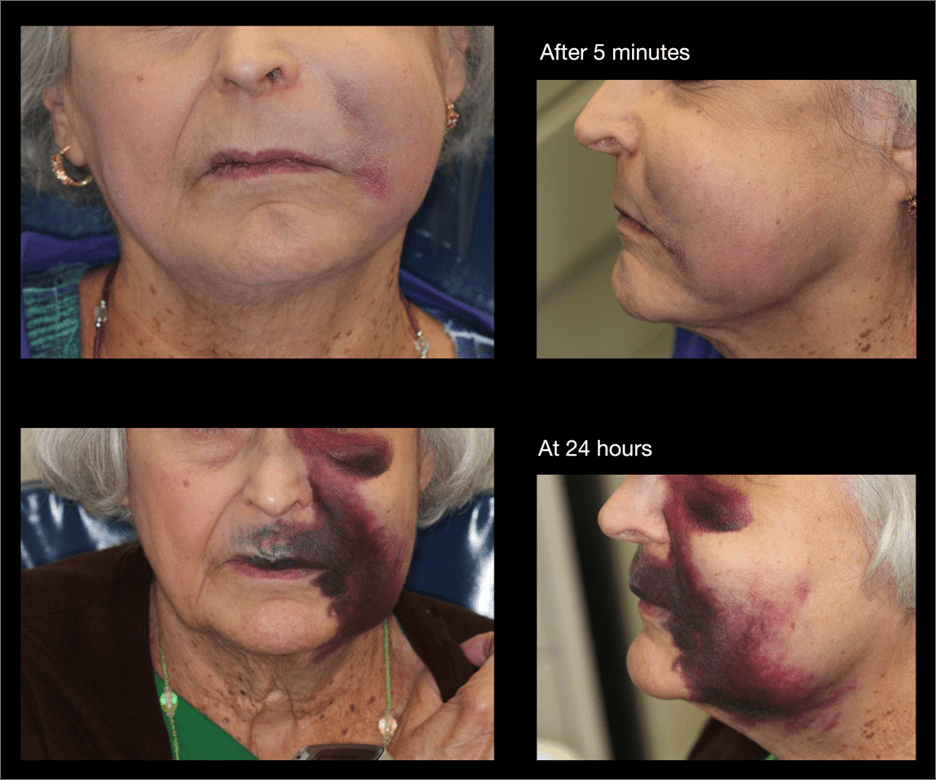

Among all endodontic complications, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) accidents evoke perhaps the strongest emotional response. They are sudden, dramatic, and unsettling for both patient and clinician. A routine appointment can change within seconds into an acute event marked by severe pain, rapid swelling, and soft-tissue discoloration that may evolve over hours or days.

Although these accidents are often perceived as unpredictable, clinical experience and published data reveal consistent patterns3. Most NaOCl injuries occur in the maxilla, particularly in molars where buccal cortical bone may be thin or fenestrated. Female patients appear disproportionately represented, likely reflecting anatomical differences in bone and soft-tissue thickness. In a significant subset of cases, an unrecognized perforation, resorptive defect, open apex or bone fenestration creates a pathway for irrigant extrusion even when technique is otherwise careful.

Anatomy alone, however, does not cause a sodium hypochlorite accident. Most events result from positive pressure irrigation combined with momentary needle wedging or overly deep placement. When coronal escape of irrigant is blocked, solution follows the path of least resistance into periapical or soft tissues. The clinical presentation, immediate sharp pain during irrigation, profuse bleeding, rapidly expanding swelling, and ecchymosis, is distinct and should not be mistaken for a routine postoperative flare-up. (Fig. 1)

When an irrigation accident occurs, the clinician’s response matters enormously4. Immediate cessation of treatment and clear, calm communication are essential. Gentle irrigation with saline helps dilute residual NaOCl. Cold compresses in the initial phase, appropriate analgesia, and selective use of corticosteroids help manage inflammation and pain. Antibiotics are indicated when mucosal integrity is compromised or infection risk is elevated. Close follow-up, particularly during the first 24 to 48 hours, is critical, and advanced imaging or medical collaboration may be necessary when swelling threatens deeper fascial spaces.

Despite the alarming early presentation, outcomes are generally favorable. With structured supportive care, most patients recover fully, even after severe tissue reactions. In many cases, the long-term impact of the event depends less on the injury itself than on how it is managed and communicated.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Safe irrigation requires respect for anatomy and constant control: avoiding needle binding, maintaining distance from the working length, ensuring visible irrigant backflow, and using side-vented needles with gentle pressure. Adequate canal preparation before irrigation is essential. When risk factors such as large lesions, immature apices, or suspected fenestrations are present, modifying the irrigation strategy, or using negative-pressure systems, can significantly reduce risk. While NaOCl accidents cannot be entirely eliminated, thoughtful technique and anatomical awareness make them exceedingly uncommon.

Shaping Mishaps: When Instruments Meet Reality

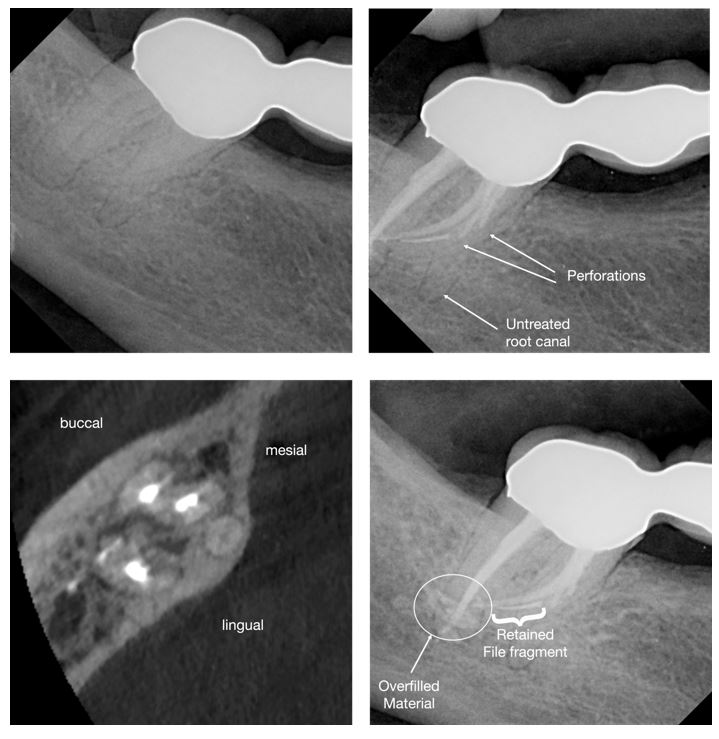

Shaping complications tend to develop more quietly than irrigation accidents. They often begin with subtle warning signs: a file that catches unexpectedly, loss of tactile feedback, or a slight deviation noticed on a radiograph. If not recognized early, these small deviations can progress to ledges, transportation, perforations, or instrument separation.

Many shaping mishaps originate during assessment. Two-dimensional radiographs, while indispensable, cannot fully represent three-dimensional root canal anatomy. Severe curvatures, apical bifurcations, S-shaped canals, and unusual molar or premolar configurations are easily underestimated. Small field-of-view CBCT has proven invaluable in complex posterior cases and can meaningfully alter treatment planning before irreversible steps are taken. (Fig. 2)

Insufficient glide-path preparation remains another major contributor. Contemporary nickel–titanium systems are remarkably capable, but they cannot compensate for a canal that lacks a smooth, reproducible pathway5. Without an adequate glide path, rotary or reciprocating instruments are subjected to increased torsional and cyclic stresses. In addition to classic torsional failure and cyclic fatigue, emerging evidence highlights torsional fatigue as a combined failure mechanism affecting modern instruments.

Instrument fracture remains one of the most anxiety-provoking events in endodontic practice. Yet presence of a retained instrument fragment itself is not synonymous with failure6. The prognosis depends heavily on fragment location, canal anatomy, remaining tooth structure, and the quality of disinfection achieved prior to separation. Aggressive retrieval attempts, particularly without magnification or appropriate training, can convert a manageable complication into perforation, root fracture, or tooth loss.

When a file fractures, the most important immediate step is restraint. Clinicians must review anatomy and obtain additional imaging when necessary. The next step is to evaluate whether retrieval, bypassing, retention, or referral is most appropriate preserves both the tooth and the clinician’s judgment. Transparent communication with the patient is essential. Referral, when warranted, reflects professionalism rather than inadequacy.

Preventing shaping mishaps relies on respect for anatomy, for instruments, and for one’s own limits. Establishing a reliable glide path, allowing files to cut without force, maintaining lubrication and irrigation, and limiting instrument reuse are all critical. Single-use protocols remain the safest option in challenging anatomy. Knowing when not to proceed is a hallmark of clinical maturity.

The Path Forward

Endodontic complications are never welcome, but they are powerful teachers. They remind us that dentistry is not merely a technical sequence, but a dynamic interaction between biology, judgment, and human responsibility. Excellence is not defined by the absence of errors, but by the ability to recognize them early, respond thoughtfully, and recover in a way that prioritizes patient safety and trust.

Clinicians may focus on procedural errors such as the ones described here while not considering other unfavorable outcomes such as life-threatening infections7 or even not recognizing a neoplasm. Irrespective, when we think that everything goes wrong, the most important action may be the simplest: pause, reassess, and proceed deliberately. Complications are not the end of the road, they are opportunities to refine judgment, deepen understanding, and deliver better care for our patients.

References

1 Torabinejad M, Sabeti M (eds). Management of Endodontic Complications. 1st edn, 2023, Quintessence, Batavia, IL, USA

2 Dahlström L, Lindwall O, Rystedt H, Reit C. ‘Working in the dark’: Swedish general dental practitioners on the complexity of root canal treatment. Int Endod J 2017;50:636-645

3 Cho-Kee D, Basrani BR, Vera J, Ordinola-Zapata R, Aguilar RR. Sodium Hypochlorite Accidents: A Retrospective Case-series Analysis of CBCT Imaging and Clinician Surveys. J Endod 2025 51:1485-1489.

4 Farook SA, Shah V, Lenouvel D, Sheikh O, Sadiq Z, Cascarini L, Webb R. Guidelines for management of sodium hypochlorite extrusion injuries. Br Dent J 2014;217:679-84.

5 Plotino G, Nagendrababu V, Bukiet F, Grande NM, Veettil SK, De-Deus G, Aly Ahmed HM. Influence of Negotiation, Glide Path, and Preflaring Procedures on Root Canal Shaping-Terminology, Basic Concepts, and a Systematic Review. J Endod 2020;46:707-729.

6 Parashos P, Messer HH. Rotary NiTi instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod 2006;32:1031-43.

7 Shemesh A, Yitzhak A, Ben Itzhak J, Azizi H, Solomonov M. Ludwig Angina after First Aid Treatment: Possible Etiologies and Prevention-Case Report. J Endod 2019;45:79-82.

Figure 1: Clinical impression of a sodium hypochlorite accident. Photographs show the dramatic progression in the first 24 hours.

(Case courtesy Dr. Ray)

Figure 2: Clinical example of a mandibular second molar with unusual anatomy. Postoperative radiographs show the presence of a retained instrument fragment along with further procedural errors.